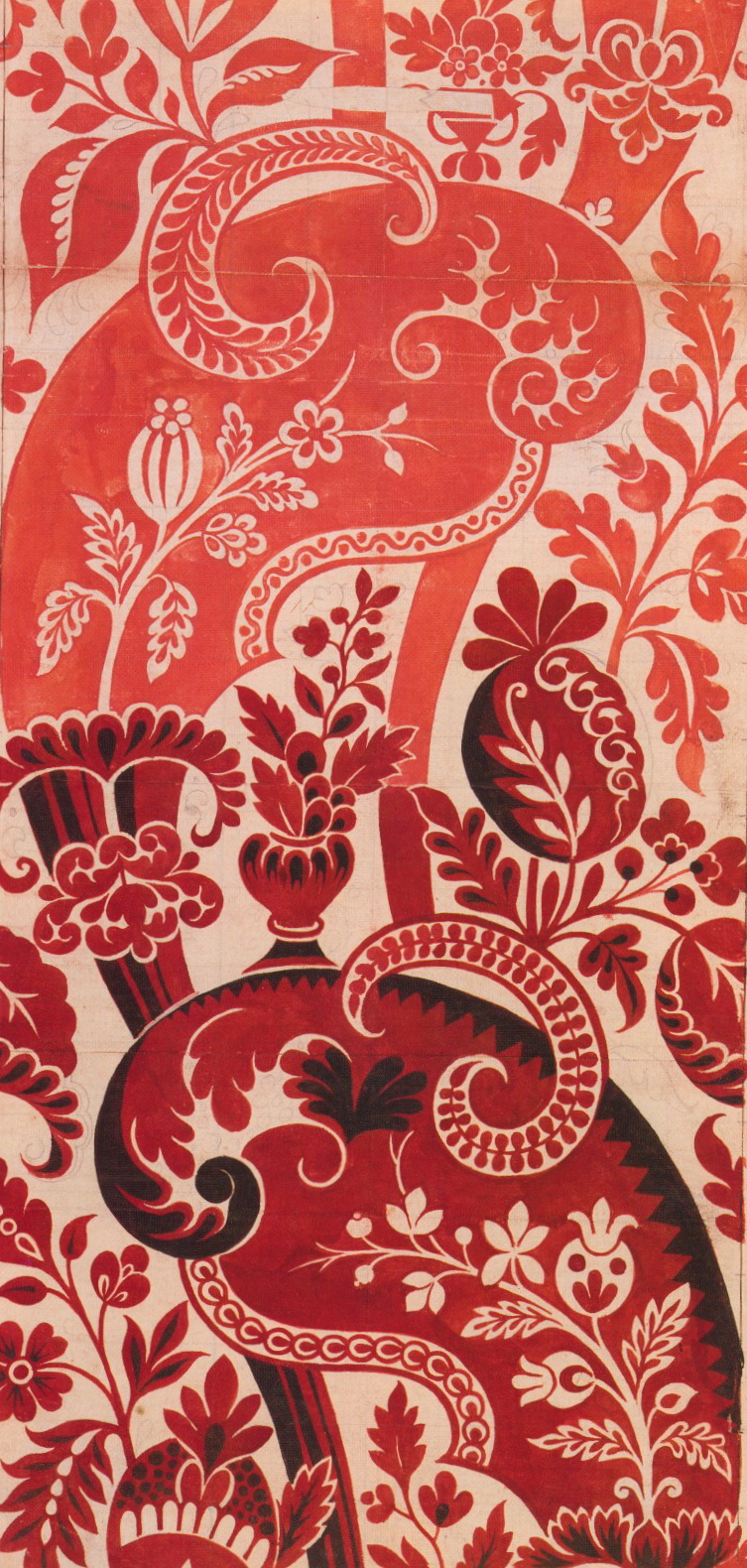

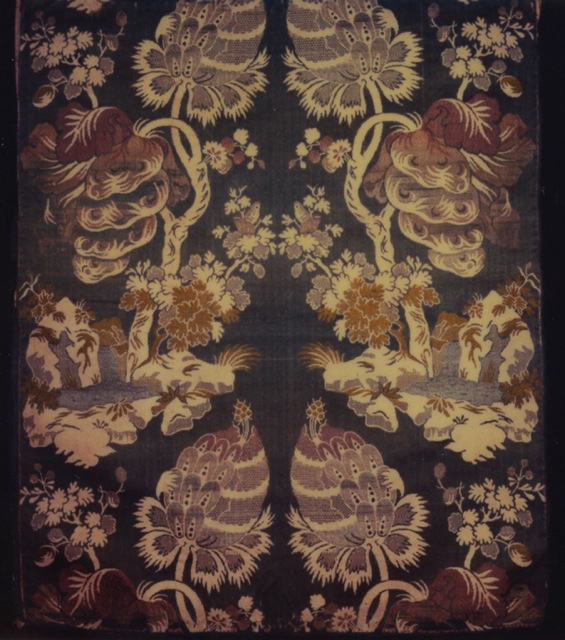

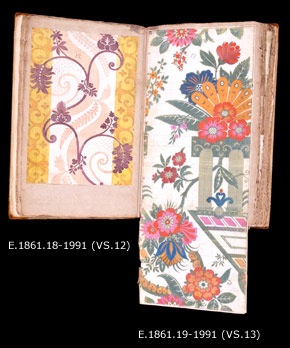

James Leman, silk design, 1717

James Leman, silk design, 1717

Watercolor on paper

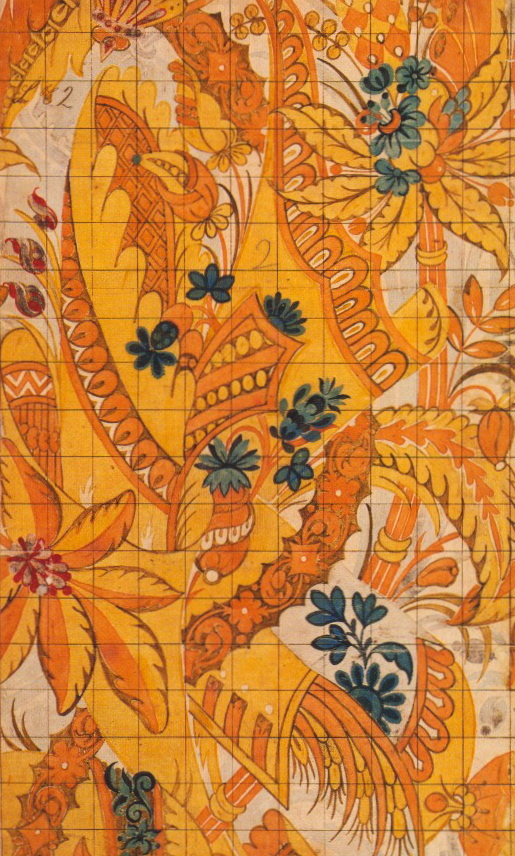

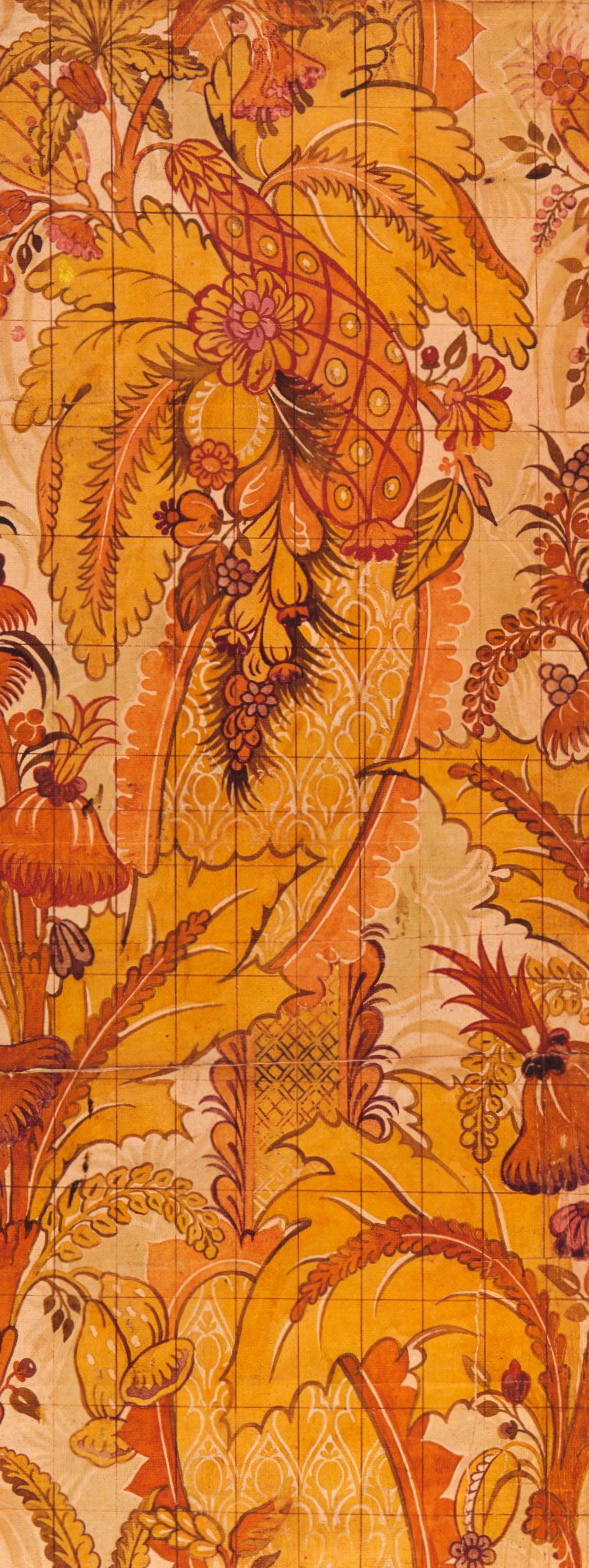

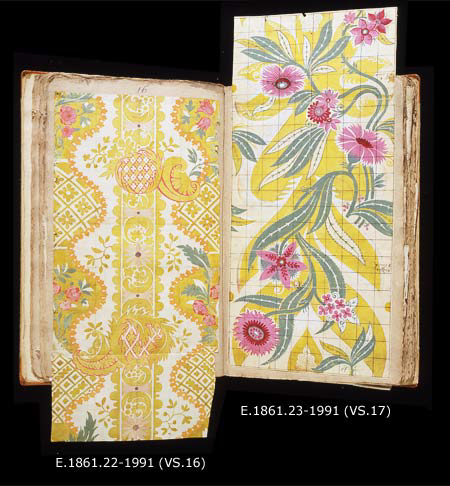

James Leman (c.1688-1745) was one of the pre-eminent designers of silk textiles in the first half of the 18th century in England. In addition to being a designer, Leman was also a silk manufacturer and likely a master weaver as well, a combination of talents that was common in the silk-weaving industry in Lyons but rare in England. James Leman, of Huguenot descent, was the son of Peter Leman, a master weaver. He apprenticed to his father in 1702 and took over the family business in 1706. Ninety-seven of Leman’s watercolor designs, bound in an original Spitalfields design book and dated 1706-1730, are in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. It’s hard to believe that these designs, the color so fresh and vibrant, and the patterns so modern, are 300 years old. Note that the yellows and oranges in the watercolors represent various colors of metallic threads.

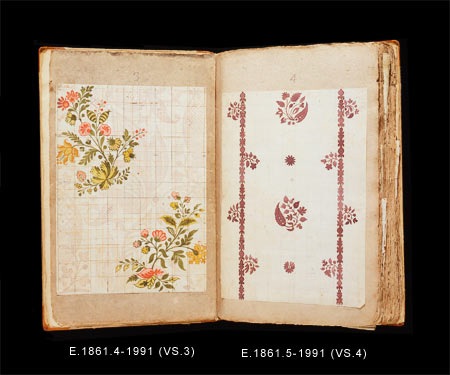

Album of silk designs by James Leman in the Victoria & Albert Museum

Various dates, 1706-1730, watercolor on paper

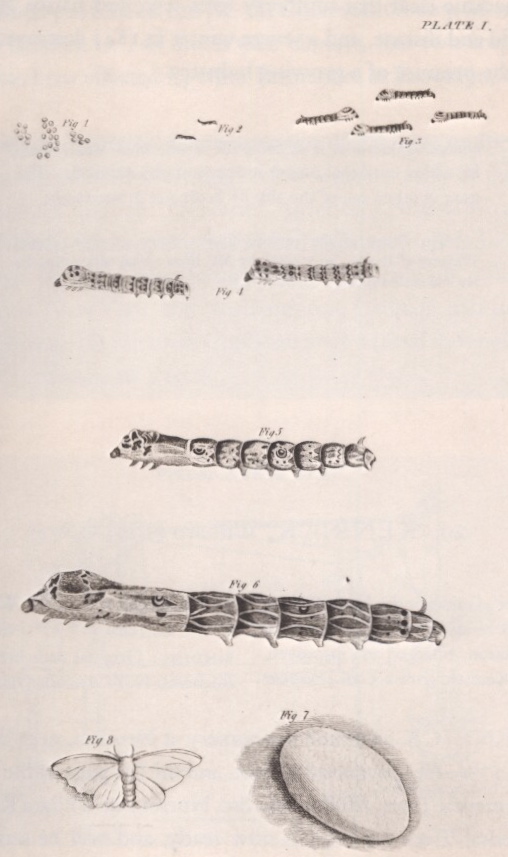

The influence of the Huguenot emigres on England’s textile industry was enormous, because they brought their weaving skills with them. Until that point the English silk-weaving industry had been quite small—with the expertise of the Huguenot weavers, it blossomed. The Huguenots, Protestants from France, were subject to several waves of persecution in the 16th and 17th centuries. They left France by the thousands and contributed greatly to the textile industries of Britain, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. In reaction to the arrival of an early wave of Huguenot emigres in search of employment, King James I, who ascended to the throne of England in 1603, and was an admirer of silk garments, attempted to introduce sericulture to England. James commissioned a book on the subject and provided the landed gentry with a supply of mulberry seeds and trees. The experiment was not a success, and weavers had to continue to rely on imported silk, which, as the demand grew, Britain obtained from China, Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

The life cycle of the silk worm, 1831

lithograph, signed W.S. & J.B. Pendelton of Boston

from Jonathan Cobb’s Manual containing information respecting the growth of the Mulberry Tree

An interesting aside to the Huguenot story is that one of the most prominent Huguenot families to settle in England was the Courtaulds, who fled from France in the 1680s and later became silk weavers. A descendant of this family, Samuel Courtauld, who took control of the company in 1908 (the firm invented rayon, a synthetic silk, in 1910), achieved great renown as an art collector. In 1932 he founded the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, to which he bequeathed his collection upon his death in 1947.

James Leman, silk design, 1706/7

James Leman, silk design, 1706/7

Watercolor on paper

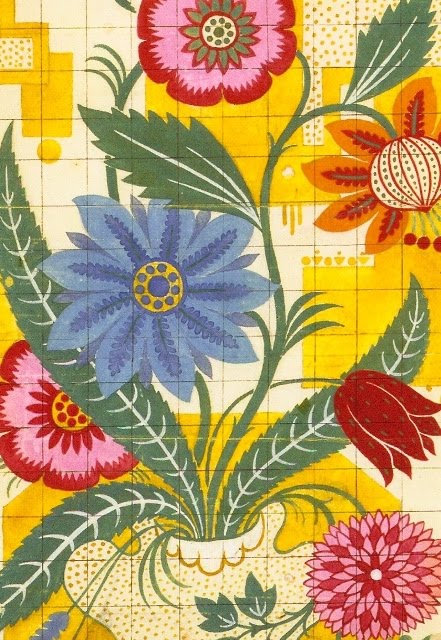

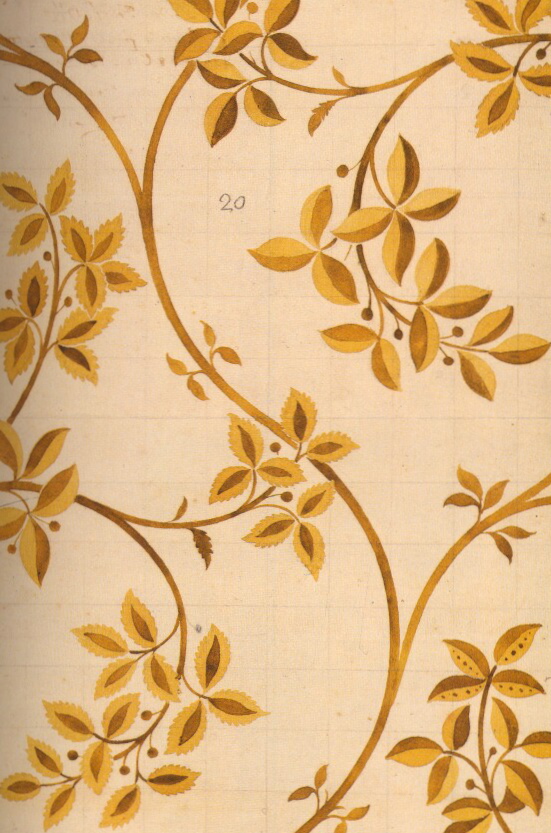

James Leman, silk design, 1710

James Leman, silk design, 1710

Watercolor on paper

James Leman, silk design, 1711/12

James Leman, silk design, 1711/12

Watercolor on paper

By 1700 the center of silk manufacturing in England was in Spitalfields, now part of East London. Spitalfields has had an illustrious history. On the site of what was in Roman times a cemetery, England’s largest medieval hospital was constructed—The New Hospital of St Mary without Bishopgate—in 1197. The name Spitalfields is a contraction of “hospital fields.” The area went through many transformations, eventually becoming a textile center—first for laundresses, then for calico dyeing, then, in the 18th century, silk weaving. After the silk-weaving industry failed in the 1820s, the area declined and eventually became a center for furniture building, boot-making and later, tailoring. In Victorian times it became seedier still, and was famous for grisly murders by Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel Strangler. The area is largely gentrified now, and when the historic Spitalfields Market area underwent a major renovation in the 1990s, the Roman cemetery became an important archeological dig and yielded many stunning artifacts, including sarcophagi with human remains.

Court dress, British, c. 1750

Court dress, British, c. 1750

Silk, metallic thread

Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The development of the silk industry in 18th century England paralleled that of the rest of the decorative arts in England—following a trajectory from simplicity through the development of the elaborate English Rococo style, then back to Neoclassical. Over the course of the century, design influences went back and forth across the English Channel, each decade brought stylistic changes. At the beginning of the 18th century, designers began to leave behind the excesses of the later 17th century—patterns became less exotic and more naturalistic. In the 1730s french silk designer Jean Revel (1684-1751) invented a radical new technique, points rentrés, a method that enabled the weavers to create shading. These three-dimensional patterns were often woven on a plain silk background to better show off the larger, bolder, designs.

Fabric in the style of Jean Revel, c.1733-35

Fabric in the style of Jean Revel, c.1733-35

The Art Institute of Chicago

In the 1740s, the pendulum swung again, the English “flowered silks” style emerged with more naturalistic botanical detail, in clear, soft colors on plain backgrounds. By mid-century French influence returned and through the 1750s and 1760s more background pattern re-emerged, designs became more stylized, the fabrics became stiffer with more metallic threads. By the 1770s, as styles of dress become more informal, patterns became smaller and were often combined with stripes. By the end of the century, Neoclassic patterns dominated.

As a manufacturer, James Leman employed other silk designers: two of the best known are Christopher Baudouin and Joseph Dandridge.

Christopher Baudouin, silk design, 1718

Christopher Baudouin, silk design, 1718

Watercolor on paper

Joseph Dandridge, silk design, 1718

Joseph Dandridge, silk design, 1718

Watercolor on paper

Moving towards the mid-eighteenth century, another extremely important English designer began working in Spitalfields, Anna Maria Garthwaite (c.1688-1763). Garthwaite was born in Leicestershire and moved to London in 1730, where she worked freelance, producing many bold damask and floral brocade designs over the next three decades. She was interested in naturalistic floral patterns and adapted Revel’s points rentrés technique. Hundreds of her designs in watercolor have survived and are preserved in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Fortunately, several excellent examples of clothing made from her textile designs survive, and there is at least one contemporary portrait in which the sitter is wearing a dress made from a documented Garthwaite design.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, Waistcoat, 1747

Anna Maria Garthwaite, Waistcoat, 1747

Silk, wool, metallic thread

Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Robert Feke, Mrs. Charles Willing of Philadelphia, 1746

Robert Feke, Mrs. Charles Willing of Philadelphia, 1746

Oil on canvas

Fabric design, Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1743

Anna Maria Garthwaite,1742

Anna Maria Garthwaite,1742

Silk brocade

The Fashion Museum, Bath

Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1742

Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1742

Blue and silver brocaded silk

Below is a silk brocade dress, made of fabric from Garthwaite’s design, in the Museum at FIT, followed by a William Hogarth painting at The Frick Collection. I am making no claim that the sitter’s gown is a Garthwaite design, but I was struck by the similarity.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, n.d.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, n.d.

Silk damask gown

Museum at FIT, New York

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Miss Mary Edwards, 1742

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Miss Mary Edwards, 1742

Oil on canvas

The Frick Collection

All of these 18th-century brocade and damask fabrics were woven on a drawloom. These were hand looms with a system of cords that would lift certain warp threads so that when the weft thread was passed through, intricate repeat patterns could be produced. The cords were handled by a “drawboy” who sat on the top of the loom. This method was laborious, slow and took quite a bit of skill, and attempts were made improve the equipment and speed up the process. Philippe de Lasalle (1723-1804) made inroads with his invention of the semple, a device which replaced the drawboy. The semple was also removable, so it could be transferred from loom to loom, thus saving a lot of set-up time. These and other improvements led to the invention of the Jacquard loom. In 1801, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, (who at the age of twelve had apprenticed to his father as a drawboy in Lyons), devised a system of perforated cards that mechanized this procedure, and the textile industry was changed forever. In fact, the Jacquard loom was the essentially the prototype for the computer.

The British silk industry had been able to prosper and compete with the older, more established French textile industry because they benefited from various pieces of legislation aimed at protecting the British textile industry. By the 1820s, after the repeal of long-standing embargoes on imported textiles, the English textile industry collapsed and France once again dominated the field.

Wider Connections

Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, edited by Clare Browne

The Book of Silk, by Philippa Scott

Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail, by Avril Hart and Susan North

Textile Production in Europe, Silks: 1600-1800, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Very nice post.

Thanks for this very comprehensive post about James Leman and Anna Maria Garthwaite. The designs are exquisite and very contemporary. I particularly liked the subtle colour usage in the Grthwaite designs.

Thanks for very useful information.

enjoying your blog posts-

Thanks for reading VR. Look forward to exploring your site, lots of interesting connections.

I have just chanced upon these superb historical images of silk. I have never thought to even examine silk at the V and A

Jacques Latreille, my Heugenot ancestor was a silk weaver in Spittafields. To date we have not been able to find any more than which I copy below.

I am in melbourne, Australia.

Any assistance would be greatly apprecaited.

THE LATREILLES – THEIR HUGUENOT ORIGINS

JAQUES LATREILLE ( – d.1762)

PIERRE LATREILLE (b.1740 – d.1818)

Copies No 4, 5 of what follows where made as handwritten copies and have been passed on to Peter Latreille from his grandfather Henry Le M Latreille . On the back is written:

“Copied from the original manuscript in the possession of Henry C. Latreille of 5 Bloomsbury Place, London WC. ”

FAMILY TRADITIONS AND HISTORICAL FACTS compiled by (Miss) Maria Latreille

FAMILY TRADITIONS

Jaques Latreille with his wife, an only son Pierre and three daughters (Christian names unknown) fled from the S of France in consequence of their Huguenot opinions. After an ineffectual endeavour to establish a silk mill in Ireland, Jaques and his family settled in London. He took out letters of naturalization, became a Spitalfields weaver, and died (probably) in 1762. He was buried in Spitalfields. After the death of Jaques his widow and her three ? daughters returned to their native land. One of these daughters died before her mother. The elder of the two surviving daughters married, but had no children, the younger also married and had a family.

Pierre, only son of Jaques Latreille, was born at Montauban and was ten years old at the time of flight from France. In England he became a teacher of the F. language. He married twice. His first wife died shortly after their marriage. By his second wife he had a numerous family – upon the death of his mother, widow of Jaques Latreille, Pierre’s two surviving sisters quarreled about the disposition of the property, the mother having left a larger portion to the younger sister than to the elder one. The elder sister wrote to her brother urging him to return to France, and join her in an endeavour to set aside the settlement. Pierre was unable to take the journey on account of want of means, and unwilling, as he considered that he had not been kindly treated by his mother and sister. It is said that he left the letter (which is supposed to have reached him through the medium of the F. Church) unanswered.

Pierre Latreille died in 1817 or 1818.

HISTORICAL FACTS

In 1751 le Vicomte Guignard de Saint Priest was appointed Intendant of Languedoc. This man’s rigorous enforcement of measures against the Huguenots drove a crowd from their native land. In 1752 there were three separate emigrations. The fugitives directed their steps successively to Switzerland, Holland, and Ireland. (In one of these bands of unfortunates were most probably Jaques Latreille and his family. I searched unsuccessfully for the record of the death of JL in the registers of the parish church, Spitalfields. He is said to have been buried on the brick lane side of Church St. Now formerly there was a F. Church at the corner of Church St and Brick Lane (at present I believe the building is rented by Wesleyans) and he might have been interred in the ground adjoining.

As all the registers of the F. Churches are now deposited in Somerset House, the way to arrive at a certainty respecting the date of his death and burial, and also possibly the marriages of his daughters, would be to search those registers.

In Dec. 1790 a decree was passed by the F. Government restoring to the descendants of the F. Protestant Exiles, both on male and female sides, their rights as F. citizens under certain conditions. (It was probably after the passing of this decree that the widow and her daughters returned to their native land).

(signed) Maria Latreille

I found this site very interesting. My ancestors were Hugeunorts & Master Silk Weavers in Spitalfields.We have a piece of fabric which was in the family bible & I believe that this was made by either Pierre or Jeann Breillat. I live in Australia & would like to know where I can get this authenticated. I will be going to the UK & France next year.

Hi Laraine

I’m sorry if this reaches you too late, but if you take the fabric to the V&A museum on any first Tuseday of any month you can see a tectiles specialist and the should be able to authenticate it for you and maybe tell you more about it.

Hi Laraine,

Hoping that this will reach you. I have recently discovered that my great, great Grandmother is living with her grandmother Mary Brelack on the 1851 census at 7 Arundel Street, Bethnal Green. (Parish of St. Matthews, district of St. Bartholomews in Tower Hamlets.) After more investigation, Pallot’s marriage index appear to spell her mother’s name as Breillat. I would love to know how you got on and am interesting in researching this name further. (I live in the U.K.)

Hi Laraine, After further research, I have linked my family to Jean Breillat and Pierre was his father. Also, I have found a relative to Jean’s wife’s ancestry. I hope, between us, we can fill in the blanks of our mutual heritage by making contact via this site.

Hi, I am researching a friend’s family history and his 5G Grandfather is Jean Breillat, a silk weaver, whose father was Pierre Breillat married to Madeleine Le Fevre. What happened about your fabric? Was it authenticated?

Do you have any more information on these two people?

Many thanks,

Patricia

Your website is wonderful and chock full of inspiration for me. I am a quilter who loves the design elements of the 1700s, especially neoclassicism. What surprises me most about Leman’s prints is how contemporary they look in many ways. The photo of his watercolor print, dated 1710, resembles some design elements I’ve seen in fabrics from the 1920s. Anna Maria Garthwaite’s fabric designs make my heart sing!

These articles have given me a good insight into an earlier living of the following. I recently discovered that my great great great grandfather Frederic Gilkerson and his wife Mary Langley were Hand Loom weavers silk during the 1840s. If there should be anyone reading this who has a connection with these names I should be glad to hear from you. Their children were Mary Ann and Joseph who were baptised at 12 and 9 years of age at St Mathews(?) in 1843 followed by a brother George Fredrick later the same year. Fredrick Gilkerson Sen died in the Stepney Workhouse bromley by bow after being employed as a bricklayer up to the age of 79.

Fascinated by the beautiful silk patterns etc. My 4 x great gtrandfather was a silk stocking maker operating from One London Bridge – and his son became a general silk merchant towards the end of the 18th Century. I am lucky to have many of their diaries, stock lists, accounts etc – but it is lovely to see the sort of thing they would have been handling. Thanks,

mike

Readers may be interested to know I am still weaving on old spitalfields looms as well as the latest tech. The silk is now imported already thrown as we stopped trowstering 1998 along with other silk weavers on the Essex Suffolk Border. So now we dye warp & weft silk wind, warp & weave it for the great and good. There are still a few special cloths that we hand weave so all is not lost – Richard

Hi Richard

I am a MA Textiles student at London Metropolitan University and currently researching Spitalfield Huguenot community and their weaving. I would be ever so greatful if I could see the old loom you have in action and learn how it all worked. Look forward to hearing from you.

Regards

Harsha Evangeli

I am too descended from Pierre Latreille. My mohers uncle has traced the family tree back to Pierre but not beyound.Thanks for the extra details. Presumablly we had some money in those days!!

I am interested in tracing my ancesters who were weavers in the Liberties in Dublin. William Beckett was a manager of the silk weavers Atkinsons in Dublin, this company is now in N. Ireland but all their records were lost in a fire. My family are French Huguenots and are thought to have come to Ireland via London. The name may have been Becket, Becet or Bequet. I have been weaving floor rugs and wall hangings myself since he mid 1970’s.