Chinar Leaf Bowl, Kashmir, c. 1885

Chinar Leaf Bowl, Kashmir, c. 1885

Paul Walter Collection

Note: All objects shown in this post are from the Paul Walter collection unless otherwise indicated.

The Raj, the period of British occupation in India, lasted from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. During this time, the silversmiths of India produced an incredible array of beautiful luxury tableware—including tea services, bowls, goblets, ewers, cutlery, gravy boats and card cases. Initially these pieces were made as gifts and for use in the homes of the British in India. They were also exhibited widely in Europe at expositions and shows. One of these was the Paris exposition of 1878, where the tea service for 12 given by a maharaja to the visiting Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) in 1876 was on display, along with many other examples of Kashmiri silver. Indian silver soon became very sought-after in British and European markets. The London establishments Liberty & Co., Regent Street and Proctor & Co., Oxford Street, set up workshops in India to meet the demand.

Calling Card Case featuring Krishna, Madras, c. 1880

Calling Card Case featuring Krishna, Madras, c. 1880

A tradition of European silversmithing had been established in Madras and Calcutta in the 1760s, but by the 1860s the Indian silversmiths had made it their own—wedding their traditional designs and love of embellishment with objects to suit the needs of the British.

Chinar Leaf Tea Service, Kashmir, c. 1885

Chinar Leaf Tea Service, Kashmir, c. 1885

The British love affair with tea began when they came across it in China, and silver tea services had long been a staple in the elegant English home. So when the British came to India and discovered that two of Indian’s greatest natural resources were tea (from northern India) and silver, the result was inevitable.

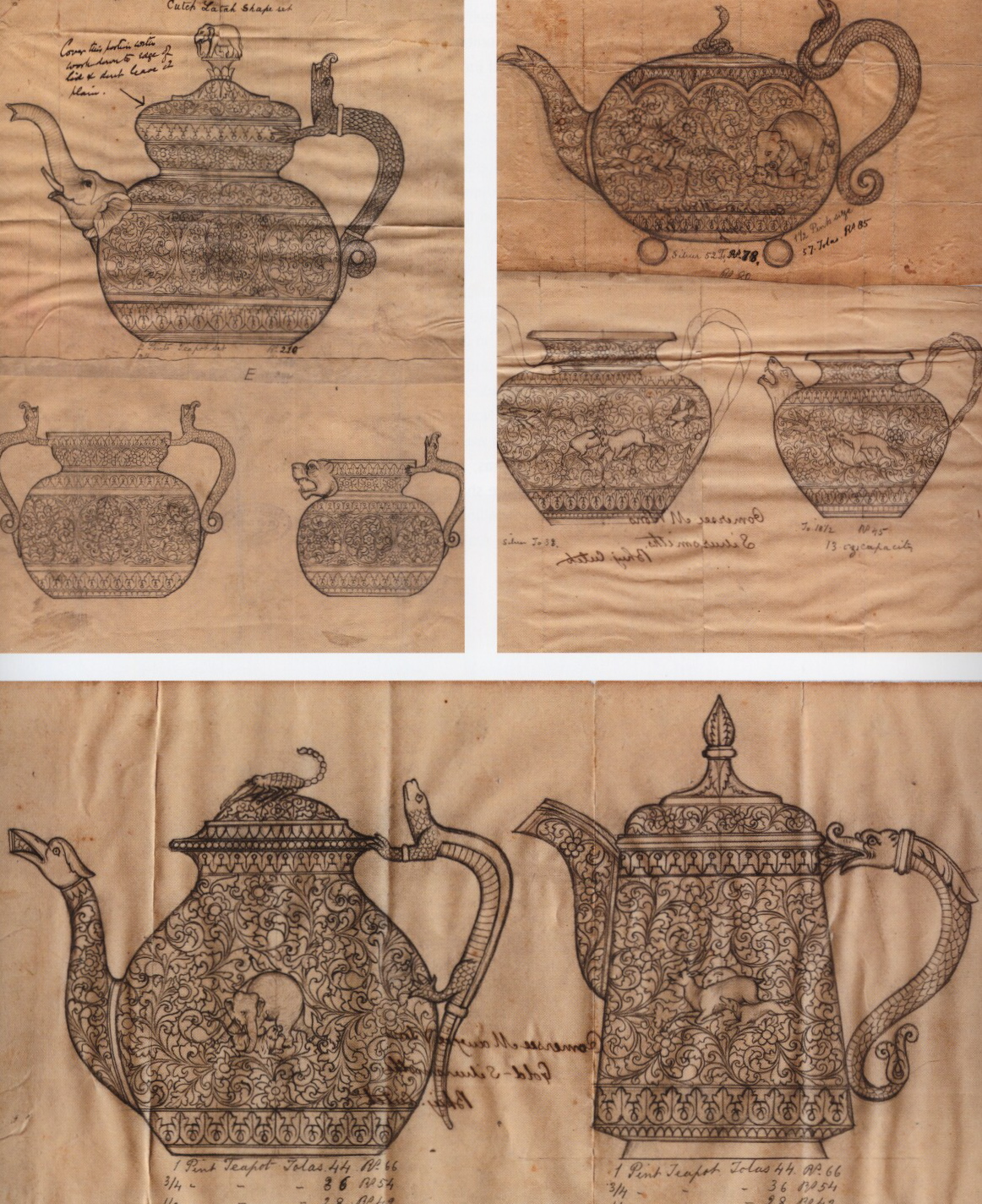

Workshop drawings of Oomersee Mawjee & Sons of Kutch

Workshop drawings of Oomersee Mawjee & Sons of Kutch

various dates, c. 1899-1904

What makes this work so fascinating is the ingenious blending of Indian motifs with western forms. These pieces have tremendous visual interest, intricate detail and texture. The Indian silversmiths created a wonderful hybrid, objects no longer strictly Indian or western, but an interesting amalgam of the two.

Kutch Silversmith at Work

Kutch Silversmith at Work

Sketch by Percy Brown after John Lockwood Kipling, 1902-03

Another fascinating aspect of silver work produced during the Raj is that the various Indian regional design traditions, adapted for these new uses, were reflected in the objects. The silver from Kutch in Gujarat, in far western India, is heavily embossed, filled with all-over curves and arabesques. The patterns appear quite abstract and are often embellished with wonderful details such as a tea pot handle fashioned in the shape of a serpent, or a spout in the form of an elephant’s head.

Kutch teapot with snake handle and elephant-head spout, c. 1880

Kutch teapot with snake handle and elephant-head spout, c. 1880

Private collection

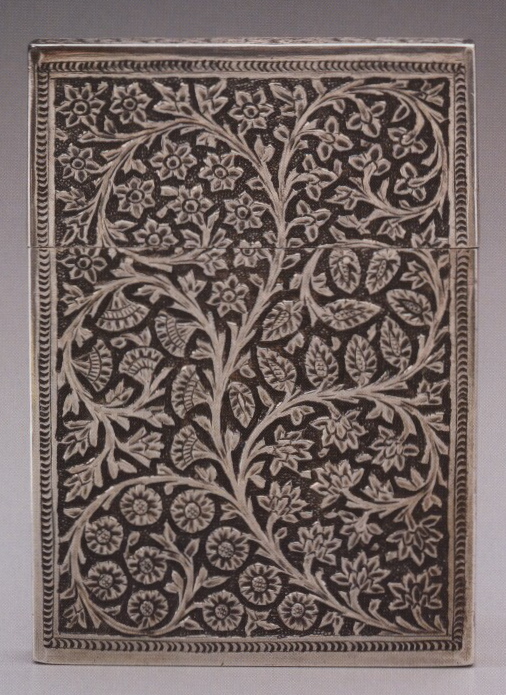

Calling Card Case with Floral Pattern, Kutch, c. 1880

Calling Card Case with Floral Pattern, Kutch, c. 1880

Four Pepper Pots, Kutch, c. 1885-1910

Four Pepper Pots, Kutch, c. 1885-1910

The silver produced in Calcutta contains very different imagery, depicting idyllic scenes from rural Bengali life—workers picking fruit, fetching water, planting or harvesting grain—as well palm trees, and an occasional cow or itinerant holy man.

Beaker with Village Scenes, Calcutta, c. 1885

Beaker with Village Scenes, Calcutta, c. 1885

The so-called Swami silver produced in Madras was filled with Hindu imagery—gods and temples, processions and scenes of music and dance. Much of this work was produced by P. Orr & Sons, a British firm established in India in 1876.

Five-piece Tea Service (detail)

Five-piece Tea Service (detail)

P. Orr & Sons, Madras, c. 1876

P. Orr & Sons showroom, Madras, c. 1899

P. Orr & Sons showroom, Madras, c. 1899

Courtesy: City Palace Museum, Udaipur

The silversmiths of Kashmir produced some of the most beautiful pieces of the period, highly embellished with botanical imagery. The British had a presence in Kashmir by the early 19th century and greatly admired the crafts of Kashmir, including the weaving. Of particular interest was the “shawl pattern” or paisley. The paisley, which looks like an elongated and stylized mango, got its name from the town of Paisley in Scotland, where many shawls of this pattern were woven. By 1887, silversmiths were incising paisley designs on plain silver against a background of intricately incised leaves, flowers and trees of the region, three of which dominated the designs. Coriander was depicted on the stem, often in continuous scroll work. The poppy, a very popular motif in Mughal art, was depicted both as closed buds and in full flower. The chinar leaf (from the Oriental plane tree (platanus orientalis) was often used in repoussé, with a background design of poppies or coriander (see a superb example at top of post.)

Lobed Stemmed Bowl, Kashmir, c. 1880

Lobed Stemmed Bowl, Kashmir, c. 1880

Chinar Leaf Plates, Kashmir, c. 1890

Chinar Leaf Plates, Kashmir, c. 1890

Until the late 20th century, the silver for the Raj, like other art of mixed heritage, was not widely valued by scholars who considered it “impure” and outside classical traditions. Fortunately, aesthetic horizons have expanded in recent years and this wonderful work is now getting the attention it deserves.

Wider Connections

Delight in Design: Indian Silver for the Raj by Vidya Dehejia

The Raj Quartet by Paul Scott

Christine,

Your post is an absolutely spectacular study of cultures intertwining, as viewed through the lens of decorative arts. The pieces are gorgeous; that stemmed goblet is sublime. I’m glad they are finally getting their due.

A couple of (minor perhaps) historical corrections for your consideration:

Technically I think the Raj period lasted from 1858, when Government of India Act was passed by British Parliament, to 1947, Indian independence (and subsequent division of Pakistan from India).

Also, from what I remember in the fascinating book A History of the World in 6 Glasses , tea plants didn’t grow in India, but were actually smuggled into India from China, as a result of the trade disputes that led to the Opium Wars (between Britain and China, 1839-1860).

, tea plants didn’t grow in India, but were actually smuggled into India from China, as a result of the trade disputes that led to the Opium Wars (between Britain and China, 1839-1860).

Thanks for your comments. At some point I’d also like to write about the silver of the Colonial Andes. The brutality of colonialism is a given, but nevertheless, another instance of the amazing melding of cultures that produced masterpieces of decorative art.

You are absolutely right about the official dates of the Raj. I was skirting the political realities and focusing on the most productive period for Indian silver of the Raj period, which was 1860-1920.

I’m sure you are correct about the tea from China, which is used to make Darjeeling tea. But a different variety of tea was native to Assam, an Indian state near the border of Burma. The British established tons of tea plantations in India in the 19th century, using both Chinese and native varieties.

Thank you for this wonderful article. I was in Gujurat not so long ago and visit a local maharjah’s palace. The silver items on display were really beautiful and finely worked.

I remember seeing a book of photographs about 19th century Indian rulers. Each one was draped with pounds of jewelry and posed among a jungle of expensive bric-a-brac. There was so much clutter that it was hard to see how beautiful each piece could be if seen alone. The lobed-stemmed bowl from Kashmir could be part of a contemporary silver exhibit that I saw at the Museum of Craft and Design while the breaker from Calcutta is just charming.

I have seen examples of colonial silver when traveling in Mexico and Peru; like the silver from India shown here, they are a unique fusion of the colonial and native traditions.

I’ve seen pictures like that too of the bedecked Indian rulers, I guess the maharajas piled on and surrounded themselves with every single precious thing they owned for those photos.

It was really astounding to me that the Indian silver in this show (Delight in Design: Indian Silver for the Raj) was being exhibited for the first time—the work was amazing, as were the many sketches they had on display alongside the finished pieces. Unfortunately the show was tucked away on an upper floor gallery on the Columbia campus and few people saw it—it deserved a show at the Met or some other well-traveled venue.

Hello, the photograph of the P Orr and Sons shop in Madras used in the book and in the above blog is from the collection of the city palace museum Udaipur. The image was loaned to Dipti Khera for her article in the said book. Please add a image courtesy line. Thanks

Christine Cariati

Hi, I am a student of Craft Design College in India. I did a document on Kashmiri Vessels. The quality of the vessels made there now are not as good as in the Kashmiri sets shown in your blog. To give a comparitive i would like your permission to use them in my document.

Also, I find your study incredible. It is very inspiring.

Very interesting and I have a pepper and salt containers in the style of the breaker from Calcutta