Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy, 1480 (detail)

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy, 1480 (detail)

Oil and tempera on poplar panel

The Frick Collection, New York

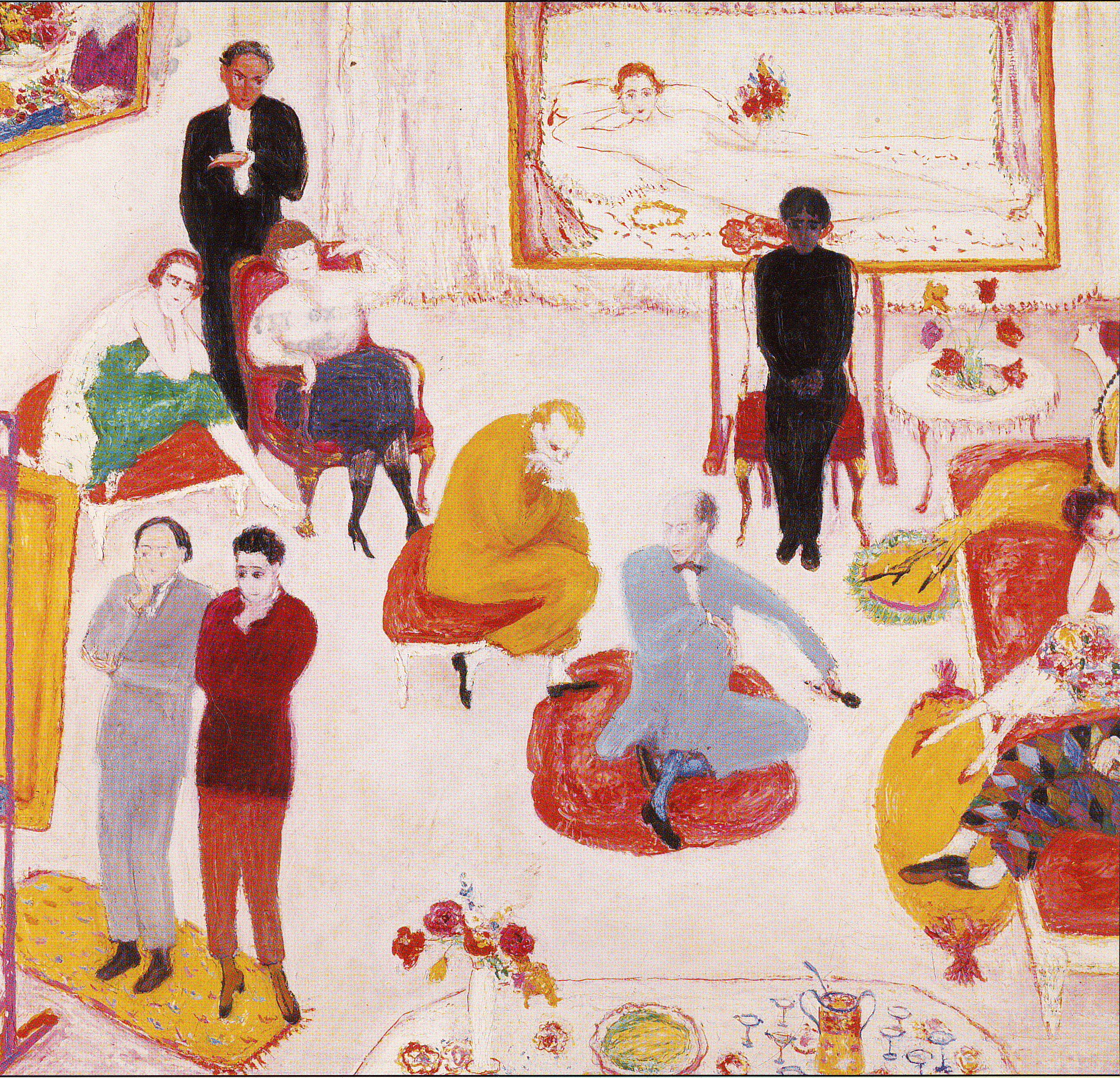

Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in Ecstasy, in the Frick Collection, has been my favorite painting since I first saw it when I was around 13 years old. When I stood in front of St. Francis for the first time it really hit me: art has power. Bellini’s painting reached out to me in a way no other painting had until that moment. It was incredibly beautiful—the composition, the color, the landscape, the compelling figure of St. Francis—everything was in perfect sync. Even on that first viewing, I knew it was rich with meaning, both tangible and symbolic, and that it would draw me back again and again. It made me want to be a painter.

I have a drawer full of post cards of it, most of them now faded and tattered (no matter, this luminous painting, in spite of technological advances, has resisted all attempts at reproduction, no photograph captures the light that emanates from this masterpiece and the color is always off—too cold, too blue, too yellow, too dark.) Every time I visit the Frick, I buy another post card, as witness to the fact that I was fortunate to see it again and because I always want to take a little piece of it home with me. When I lived in New York, I would drop in for a few minutes whenever possible to spend some quiet moments in its light. Now, when I visit New York, it’s always the first stop on my itinerary. (Obviously the Frick is filled with treasures—but St. Francis is always the first and last painting I visit.)

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy

acquired by H.C. Frick, 1915

Some years ago, I was surprised to notice that the title of the painting had been changed to St. Francis in the Desert. At first, I was tempted to seek an explanation, but then decided I didn’t really want to know—perhaps there was some scholarly reason, the curators deciding that the setting in the desert, with all its powerful symbolism, took precedence; or perhaps there had been some error in translation that was now corrected? What I feared is that the word ecstasy was deemed too potent, too provocative. Below is the definition of ecstasy, and it seems exactly right to me:

Ecstasy: The state of being beside one’s self or rapt out of one’s self; a state in which the mind is elevated above the reach of ordinary impressions, as when under the influence of overpowering emotion; an extraordinary elevation of the spirit, as when the soul, unconscious of sensible objects, is supposed to contemplate heavenly mysteries.

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (detail)

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (detail)

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1560), a master of Venetian art, was from a family of painters. He studied in the workshop of his father, Jacopo Bellini, and in 1483 succeeded his brother Gentile Bellini as painter to the Republic. His brother-in-law was the great Andrea Mantegna. Giovanni Bellini was one of the first Italian painters to master the oil painting techniques perfected in Northern Europe by the early Netherlandish painters, Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (details)

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (details)

In St. Francis, as in his other sacred paintings, Bellini imbues the landscape with spiritual meaning. For Bellini, landscape did not only set the emotional tone and dictate the composition—it was symbolic of God’s presence in all of nature. Set in this profound landscape is the figure of St. Francis, slightly to the right of center, leaning back, arms open, gazing upward toward the mysterious light in the upper left-hand corner. The laurel tree, symbol of Christ’s cross, trembles and glows in this light and leans into the picture, towards St. Francis. The painting is filled with symbols of Christ’s Passion—the skull, the crown of thorns, the Bible, the grapevines. Every rock, animal and flower holds symbolic meaning for the Franciscan scholar. St. Francis stands barefoot, his sandals removed—he is standing on sacred ground.

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (detail)

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy (detail)

St. Francis is believed to have received the Stigmata in September of 1224 on Mount Alverna in the Apennines, where he retreated to pray and fast in preparation for Michaelmas. St. Francis wanted to bear the signs of the Passion so he could better understand Christ’s suffering, and to show gratitude to God for the sacrifice of his Son for humanity’s redemption. Brother Leo, witness to the event, described the moment: Suddenly he saw a vision of a seraph, a six-winged angel on a cross. This angel gave him the gift of the five wounds of Christ.

In Bellini’s painting, we see the signs of the Stigmata, but they are subtle—I see this painting not as a narrative of the event, but as a portrait of St. Francis in communication with the divine. There are two sources of light in this painting—one, the diffuse naturalistic glow that bathes the entire landscape. Every particle of air, every creature, rock and flower, vibrates with a translucent inner light. Then there is the supernatural light emanating from the upper left hand corner—this is not the powerful light that Brother Leo describes that transmitted Christ’s wounds to St. Francis—this is a spiritual illumination. St. Francis is basking in God’s light and presence—this is the “still point in the turning world” that T.S. Eliot evokes in the first of his Four Quartets, Burnt Norton:

After the kingfisher’s wing

Has answered light to light, and is silent, the light is still

At the still point of the turning world.