Tile or panel design, W.T. Copeland & Sons, Ltd. (formerly Spode), c. 1880

Tile or panel design, W.T. Copeland & Sons, Ltd. (formerly Spode), c. 1880

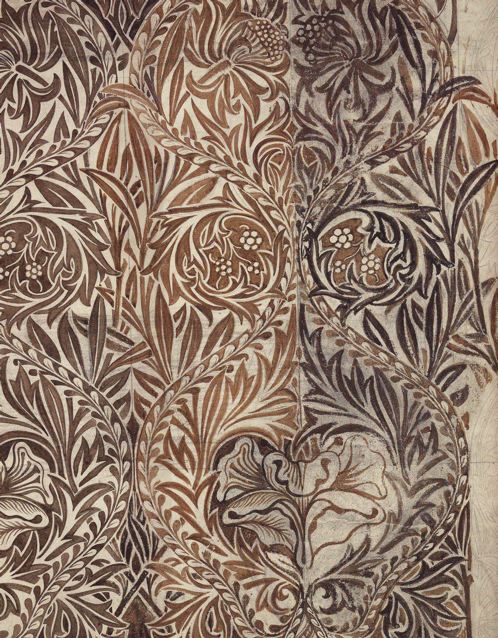

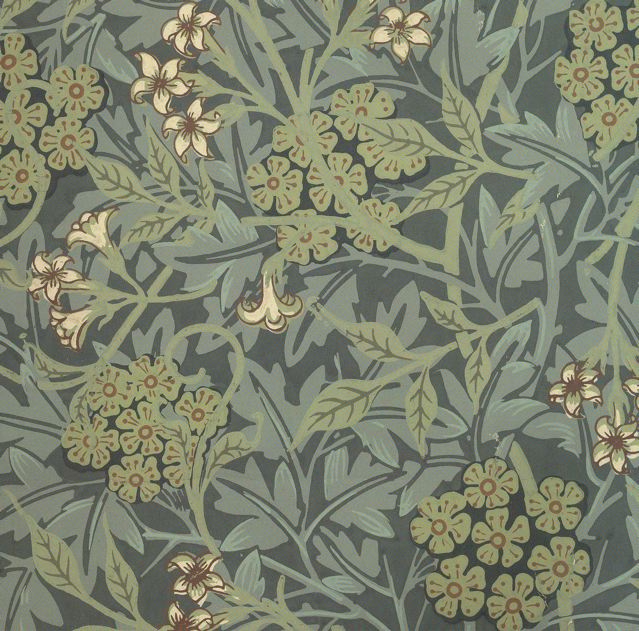

As much as I love textiles and decorative objects, I am often just as attracted to the designer’s drawings, sketches and samples as to the finished pieces. The objects, no matter how beautiful, are immutable, fixed in the here and now. On paper, it is all possibility—often the line work is graceful and sinuous, the colors are rich and vibrant, and the patterns, free of prosaic form, veer toward the abstract. The flatness of the design is part of what I find so appealing. In two dimensions, the objects are not subject to gravity, they represent that most fleeting thing—the creative impulse. They embody the alchemy of transformation, idea into image, captured in pencil, ink or watercolor.

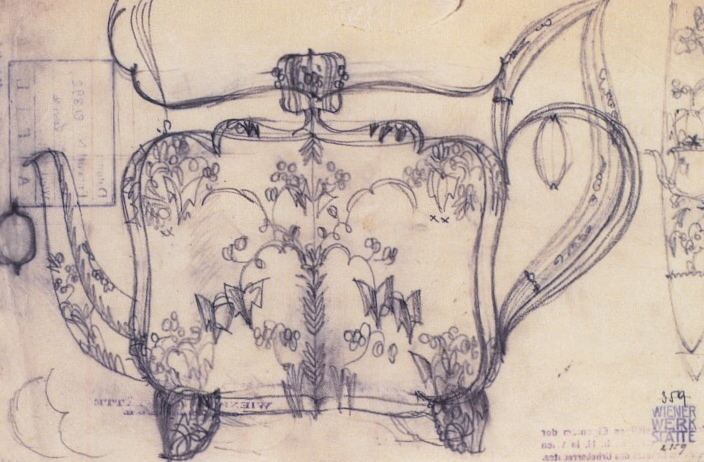

Dagobert Peche Design for a coffeepot, c. 1920

Dagobert Peche Design for a coffeepot, c. 1920

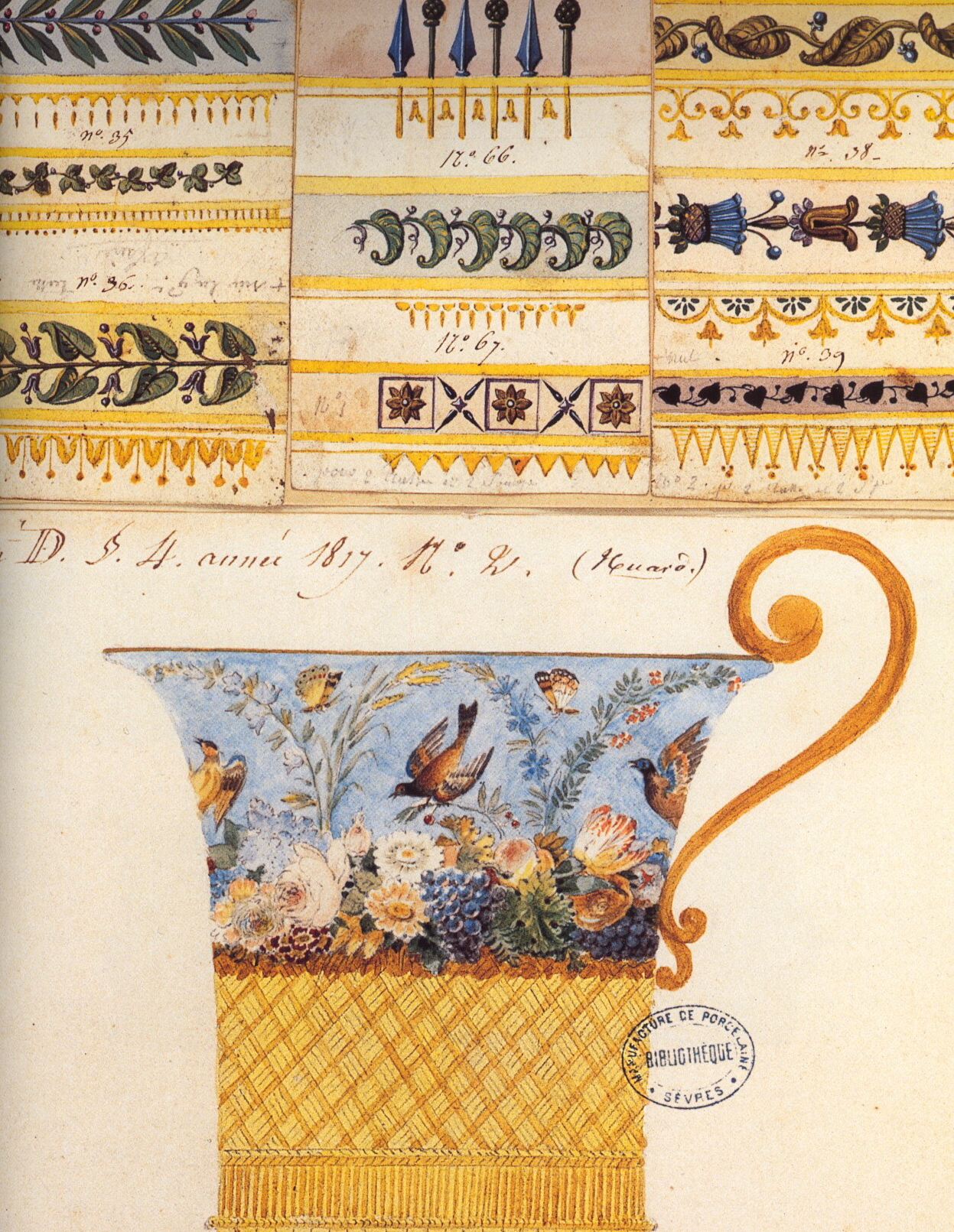

Design for a Sèvres porcelain cup, Empire period, c. 1800

Design for a Sèvres porcelain cup, Empire period, c. 1800

In some cases, as in the designs of James Leman, the delicious yellows and oranges that are so pleasing to the eye represent various shades of metallic thread— which however sumptuous and elegant in the finished textile, is a completely different visual experience. In Leman’s designs on paper, his lyrical line and masterful layering of abstracted botanical images are enhanced by the warm, saturated colors. As patterns, woven in metallic thread on a heavy silk fabric, they are breathtaking and grand, but no longer have the down to earth, fresh from the garden appeal that they have on paper.

James Leman, design for silk fabric, 1711

James Leman, design for silk fabric, 1711

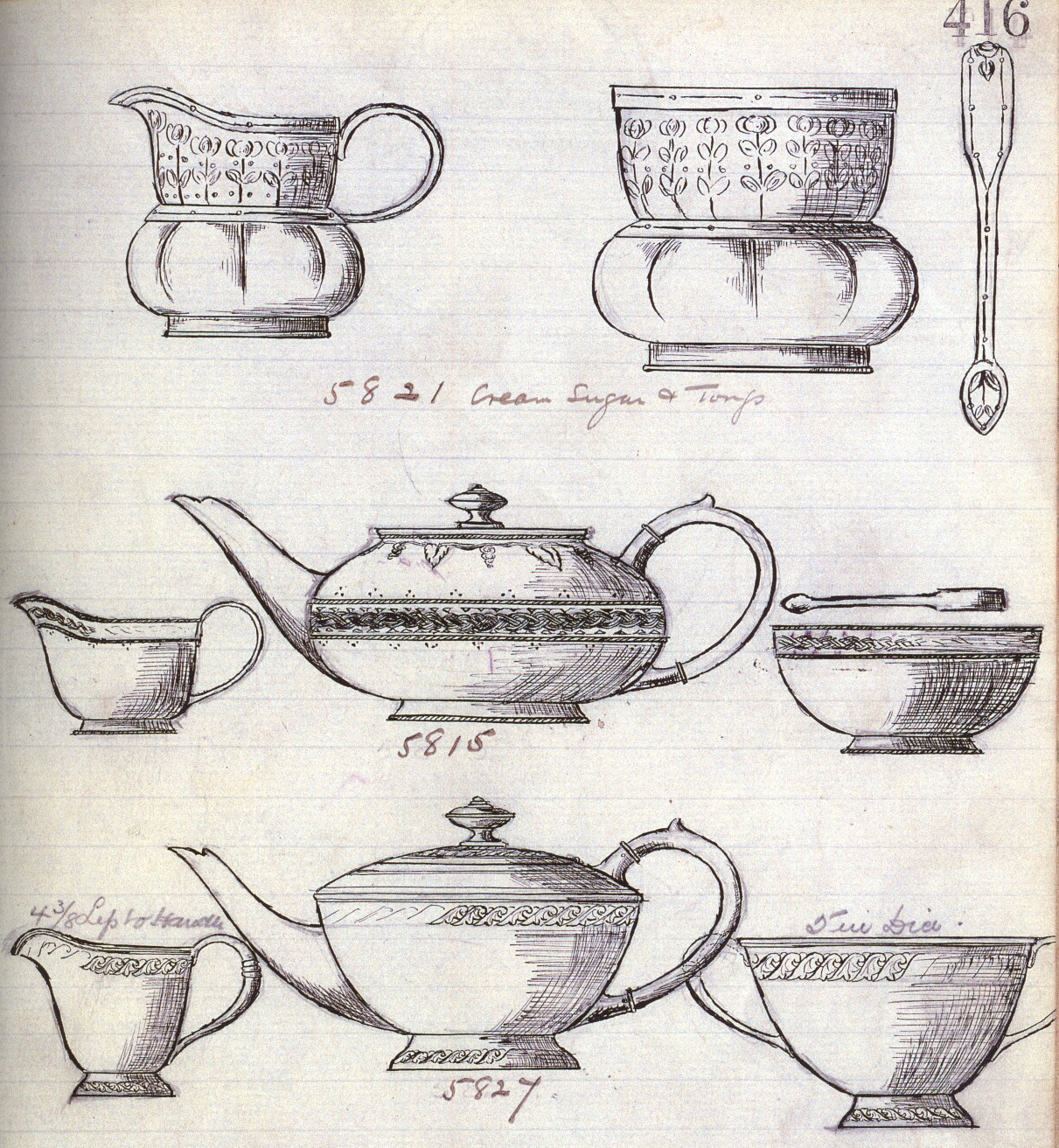

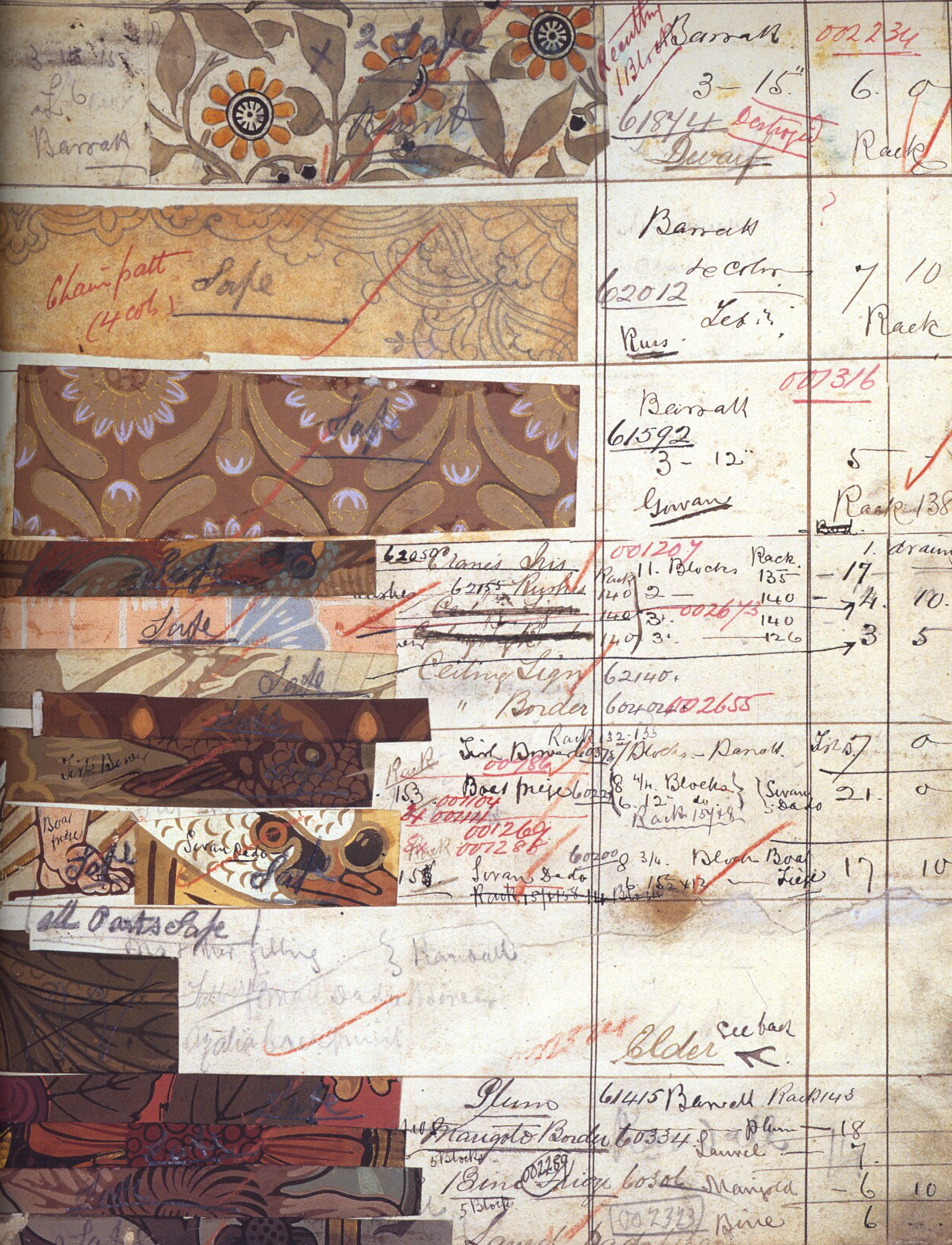

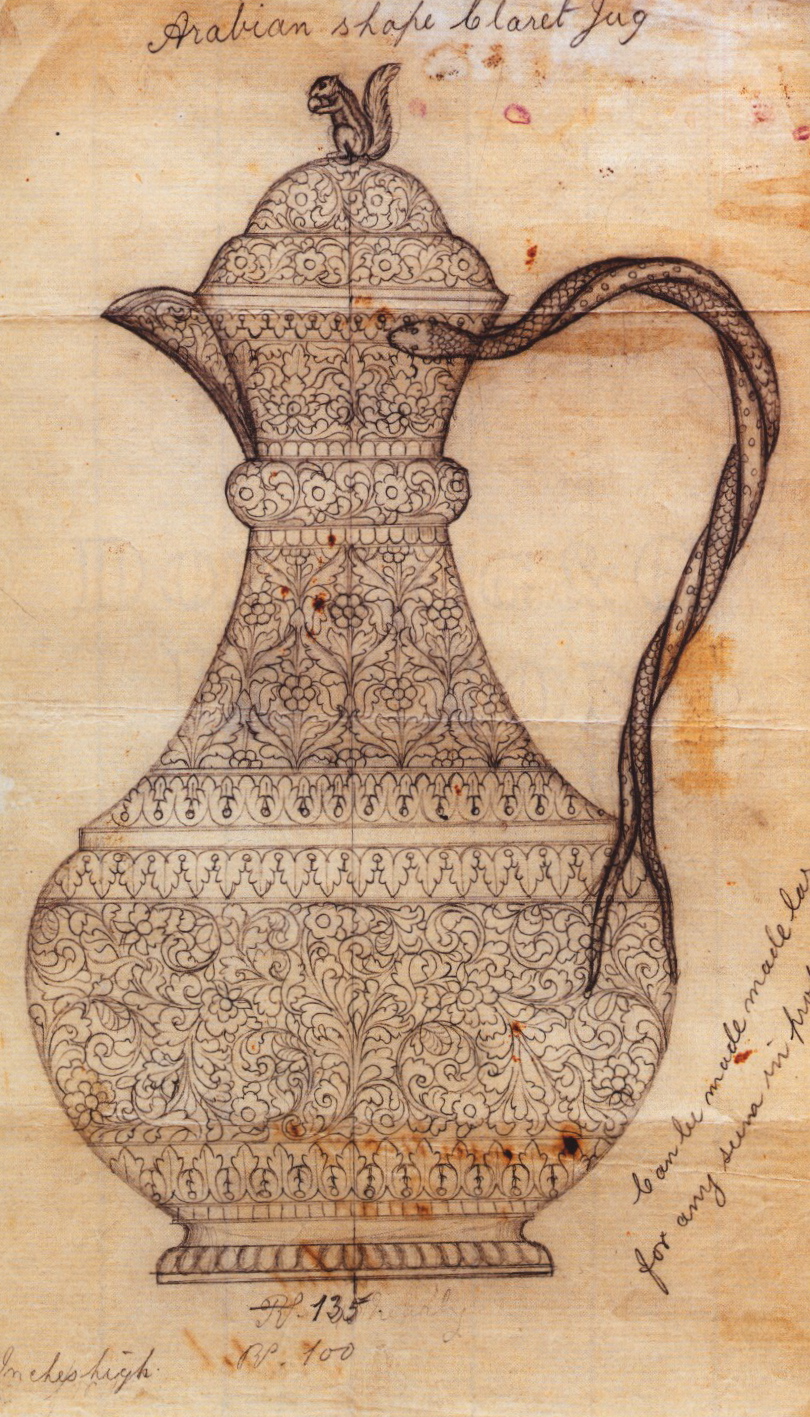

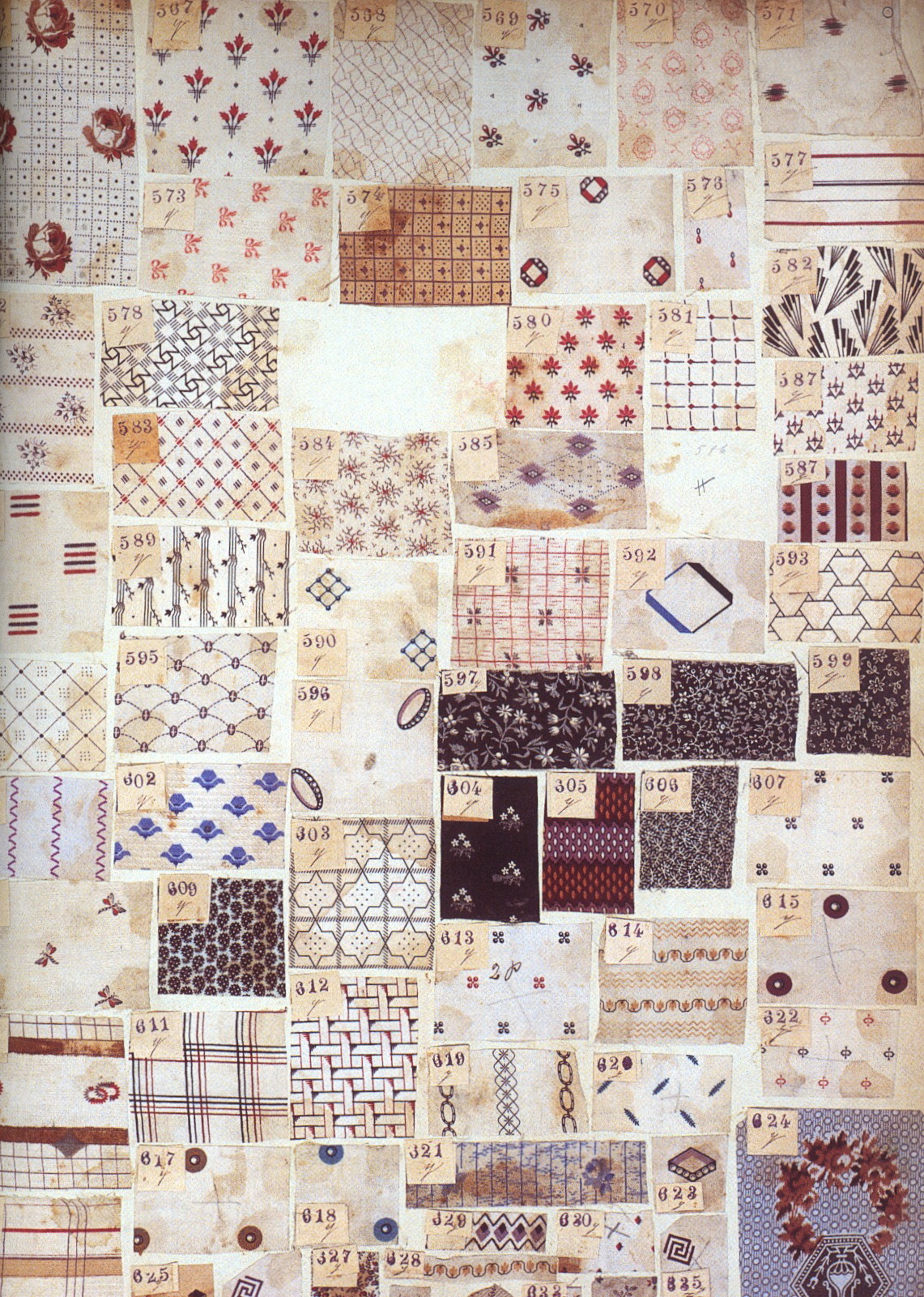

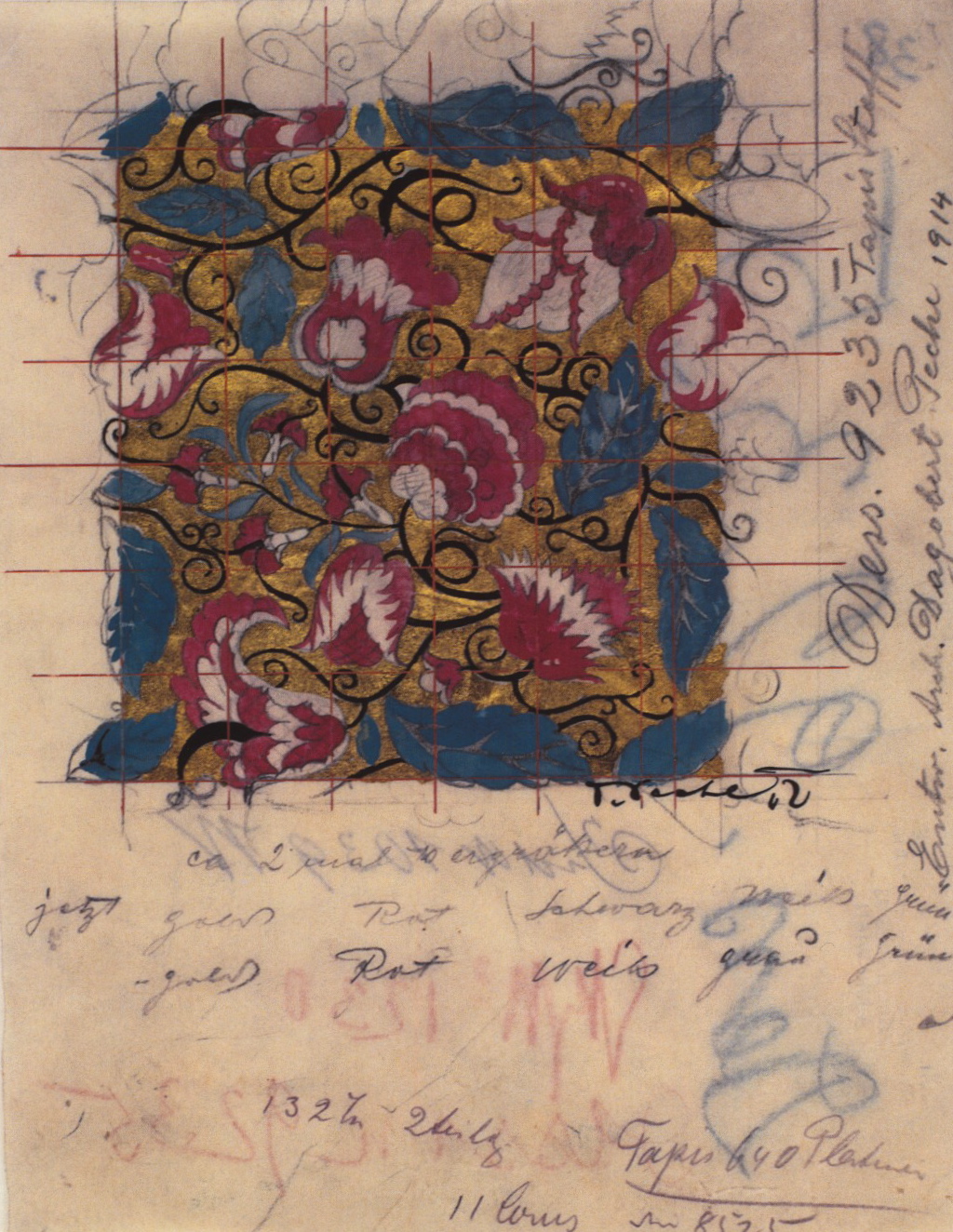

I love the annotations on many of these sketches—dates, yardages, cost calculations, style names and numbers—many are in the artist’s hand alongside the images. They are a decorative counterpoint to the design, often extremely graceful and engaging in themselves. You can also see marks and notations made by the printers, engravers, weavers and dyers—the artisans who actually executed the designs. The combination of the drawing and the notations provide a compelling history, tracing the evolution from design to finished product.

Design for candelabra, c. 1840-1873

Design for candelabra, c. 1840-1873

Elkington & Co. Ltd.

Tin-plate molds, Shoolbred, Loveridge & Shoolbred of Wolverhampton

Tin-plate molds, Shoolbred, Loveridge & Shoolbred of Wolverhampton

Tea pots, creamers and sugar bowls, Liberty archive, c. 1900-1912

Tea pots, creamers and sugar bowls, Liberty archive, c. 1900-1912

These working sketches were executed on paper, and, at the time they were created, not considered precious pieces to be treated with great care. As a result, the paper is often yellowed and brittle, and you can see smudges, folds, creases and spills. On many of them you can still see the grids and guidelines—another interesting counterpoint to the pattern and design. I don’t see these designs as mere preliminaries, inferior to a perfect, finished object. To my eye, they are works of art in themselves.

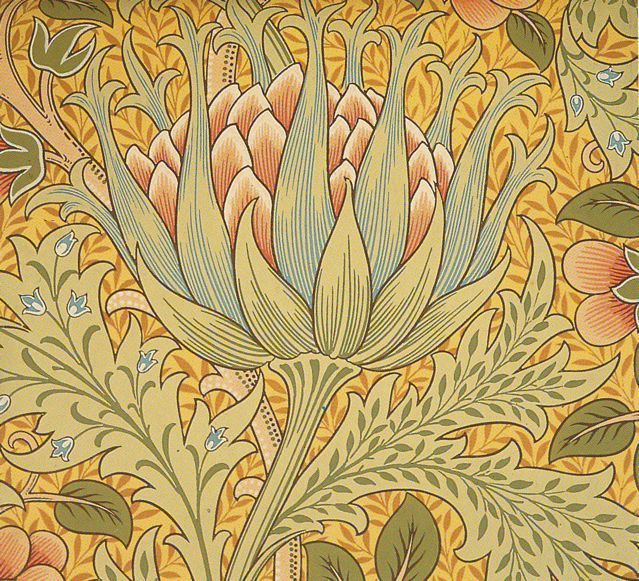

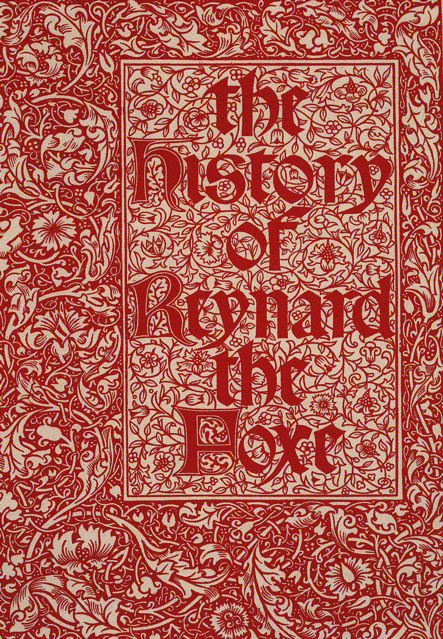

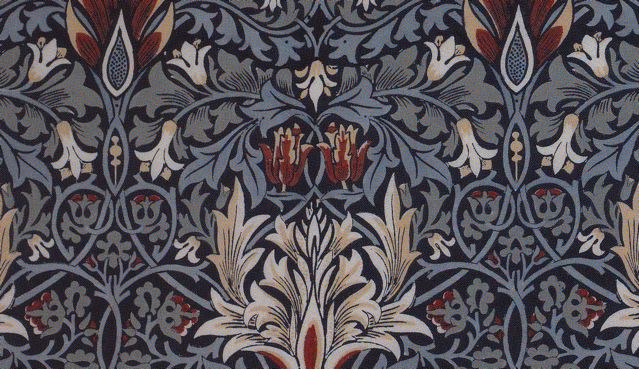

William Morris, Watercolor design for Evenlode, 1883

William Morris, Watercolor design for Evenlode, 1883

(design for cotton fabric, printed by indigo discharge)

William Morris, watercolor design for Redcar carpet, c. 1881-1885

William Morris, watercolor design for Redcar carpet, c. 1881-1885

William Morris & Co. wallpaper designs, c. 1860s

William Morris & Co. wallpaper designs, c. 1860s

I’ve restricted myself to designs for decorative objects, tableware, textiles and wallpaper and resisted the temptation to include designs for furniture, architecture and fashion. I have also deliberately not juxtaposed the drawings with the finished objects made from the sketch, because for me these stand as complete works on their own.

Design for seven-piece coffee set, Sèvres, 1899

Design for seven-piece coffee set, Sèvres, 1899

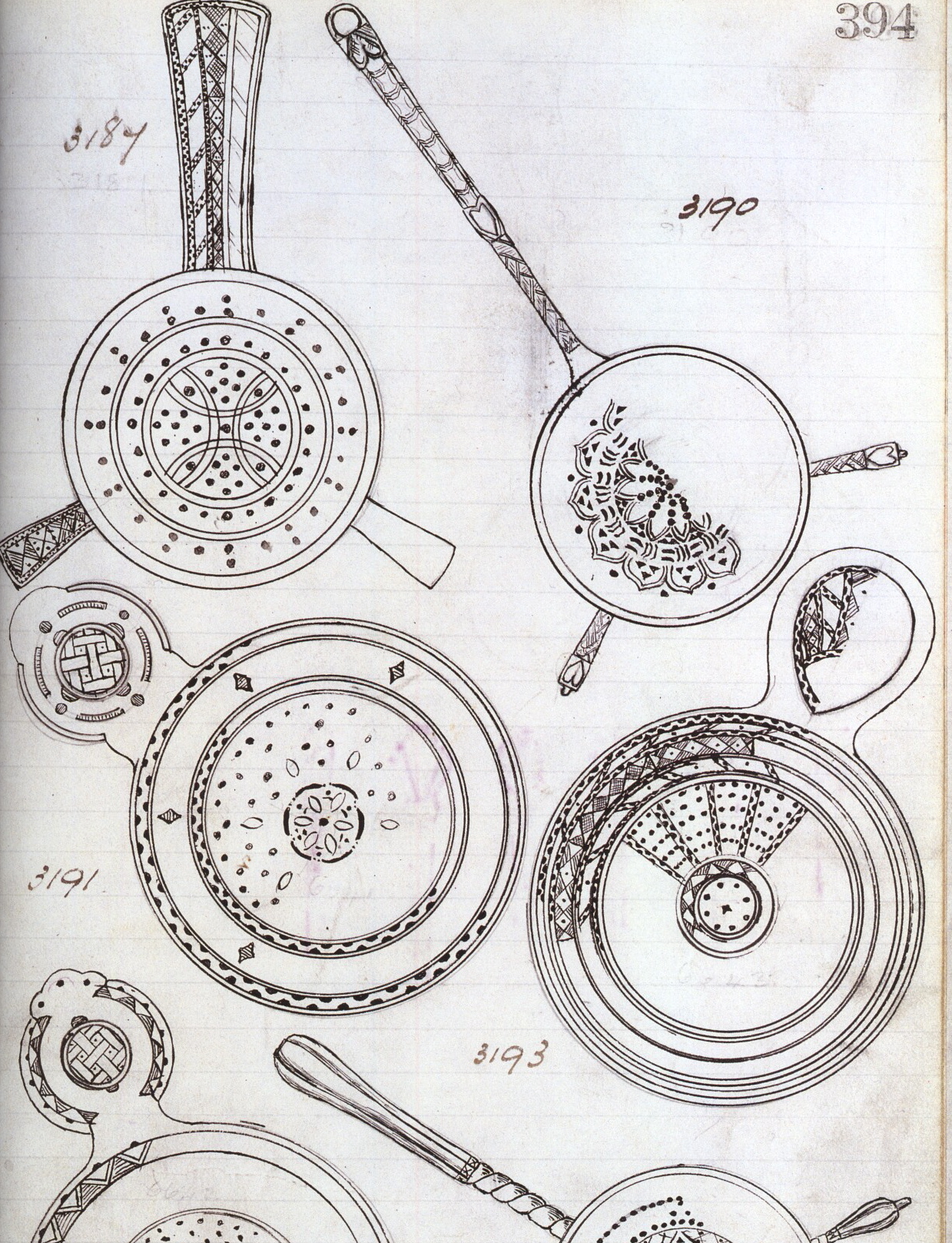

The designs below, drawn in pencil or pen and ink, are quite elegant and visually stunning. This page of designs for tea strainers is beautifully drawn, patterned and balanced—and could easily be taken for a contemporary abstract drawing.

Designs for tea strainers, c. 1900-1912

Designs for tea strainers, c. 1900-1912

Pen and ink on ruled paper, Liberty, London

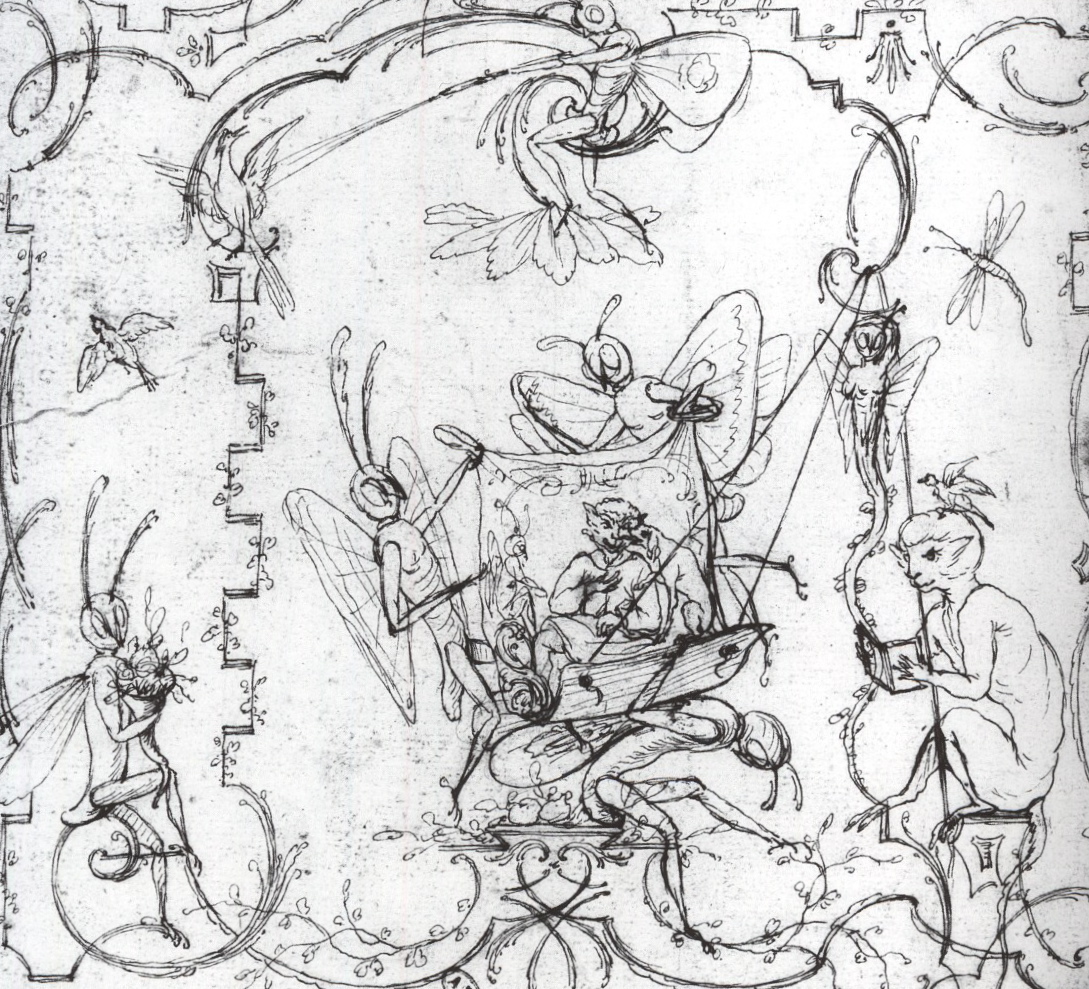

In a narrative vein, this delightful Rococo-style sketch of insect figures, for use as a decorative motif, is playful and lively.

Charles-Germain de Saint Aubin (1721-86), sketch for decorative motif

Charles-Germain de Saint Aubin (1721-86), sketch for decorative motif

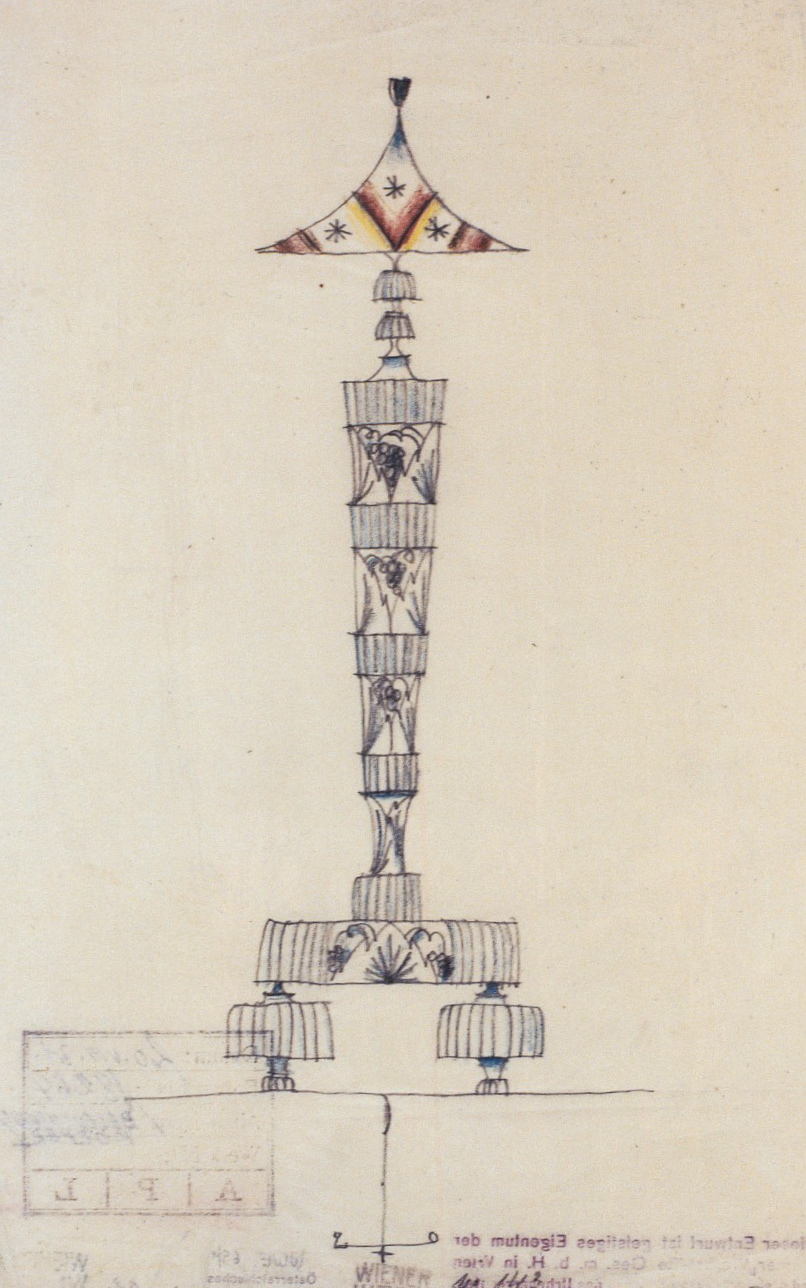

This Wiener Werkstätte floor lamp design has a figurative totem-like quality, and is drawn in a loose and graceful style. Dagobert Peche’s sketches always have a flowing, effortless hand-drawn quality—a wonderful contrast to the elegant formalism of the objects made from his designs.

Dagobert Peche, design for floor lamp, 1920

Dagobert Peche, design for floor lamp, 1920

This sketch for a graceful carafe has a very different presence than the finished piece of heavily embossed silver. As an object, the carafe has weight, volume, shine and a beautifully textured surface. The drawing, flat and decorative, has a very different, wonderful combination of elements. There is a narrative feel to it—the intricate patterning, sensuous curves, twisted serpent handle and amusing squirrel seem to be telling a story.

Arabian shape Claret jug, c. 1880

Arabian shape Claret jug, c. 1880

Workshop drawings of Oomersee Mawjee & Sons, Kutch

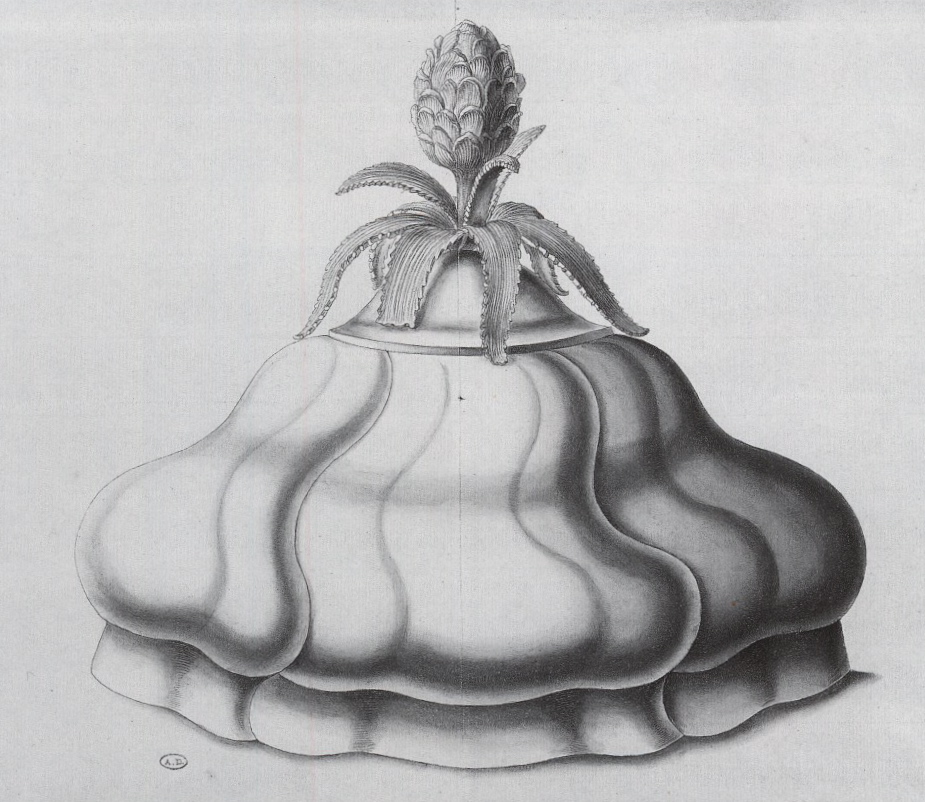

This gorgeous ink and wash drawing of a cloche has so much presence and volume. The sculptural decorative element at the top is exquisitely rendered.

Cloche, French, eighteenth century

Cloche, French, eighteenth century

Much of the inspiration for decorative objects comes from nature, as these floral designs for textiles by Anna Maria Garthwaite illustrate so beautifully. These botanical patterns, which take on a seriousness and formality when woven in silk and brocade, are exuberant on the page.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design, c. 1730

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design, c. 1730

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design, detail, c. 1730

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design, detail, c. 1730

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design (possibly a copy of a French original) detail, 1733

Anna Maria Garthwaite, silk design (possibly a copy of a French original) detail, 1733

Some of my favorite designs are for tea pots, tea cups and china patterns. They are drawn in flattened-out, foreshortened shapes to best show the designs—you can really appreciate the quality of line, pattern and detail. The decorative motifs are fanciful, lighthearted and graceful—exactly the qualities treasured in a piece of delicate porcelain.

Tea cup designs, Spode, c. 1846

Tea cup designs, Spode, c. 1846

Majolica design, Apple Blossom flower pot, Wedgewood, c. 1850-1860

Majolica design, Apple Blossom flower pot, Wedgewood, c. 1850-1860

Coffee and Tea Cups, Spode, c. 1840

Coffee and Tea Cups, Spode, c. 1840

Dagobert Peche, Design for a teapot, c. 1922

Dagobert Peche, Design for a teapot, c. 1922

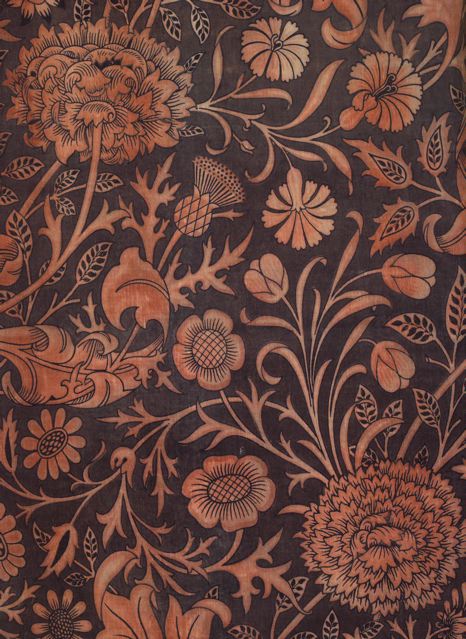

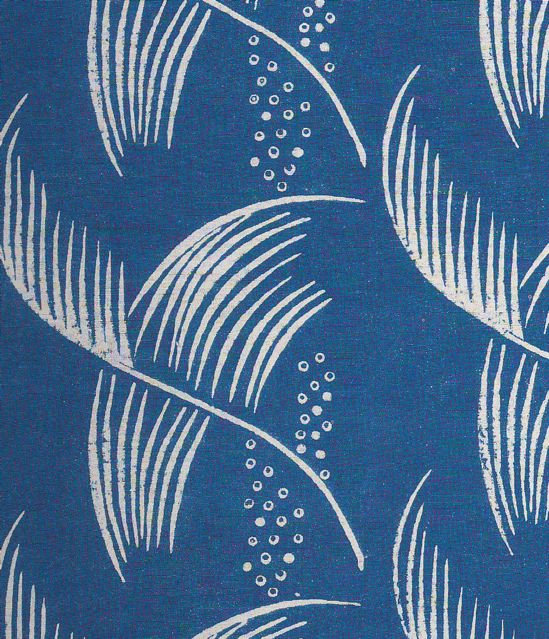

Textile designs are executed in both minimalist and very painterly styles. Often you will see only one piece of the design completed painted, with the repeats only sketched in. When the designs are for woven fabric or rugs, you sometimes see the graph paper grids they are sketched on.

Fabric designs from Lyons, France, 19th century

Fabric designs from Lyons, France, 19th century

Textile design, factory of Jean-Michel Haussmann, Colmar, 1797

Textile design, factory of Jean-Michel Haussmann, Colmar, 1797

Dagobert Peche, design for tapestry fabric for Johann Backhausen & Söhne, 1912

Dagobert Peche, design for tapestry fabric for Johann Backhausen & Söhne, 1912

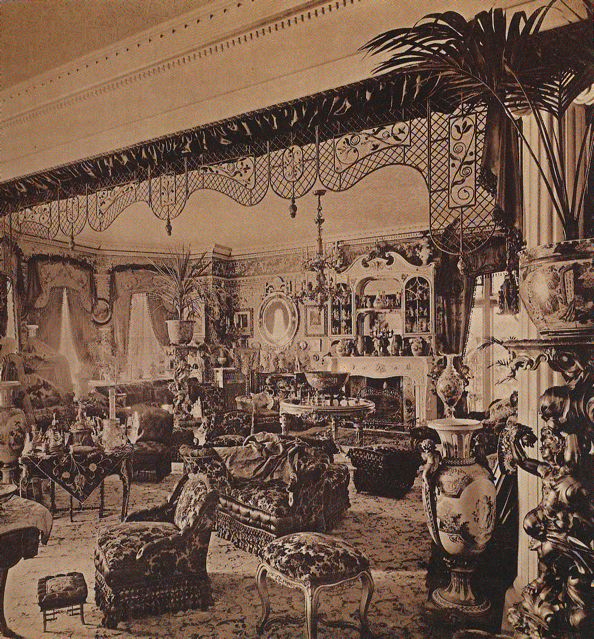

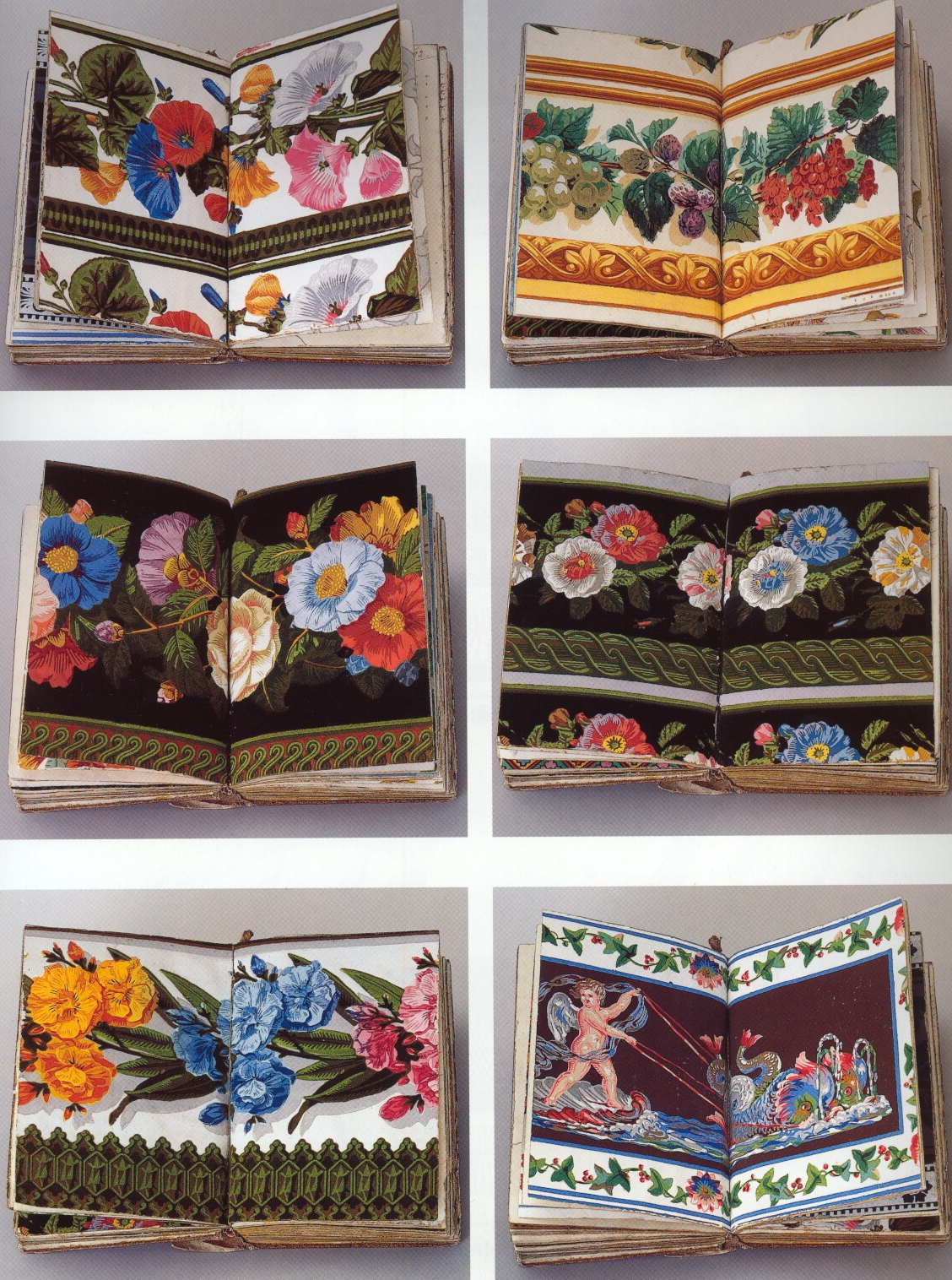

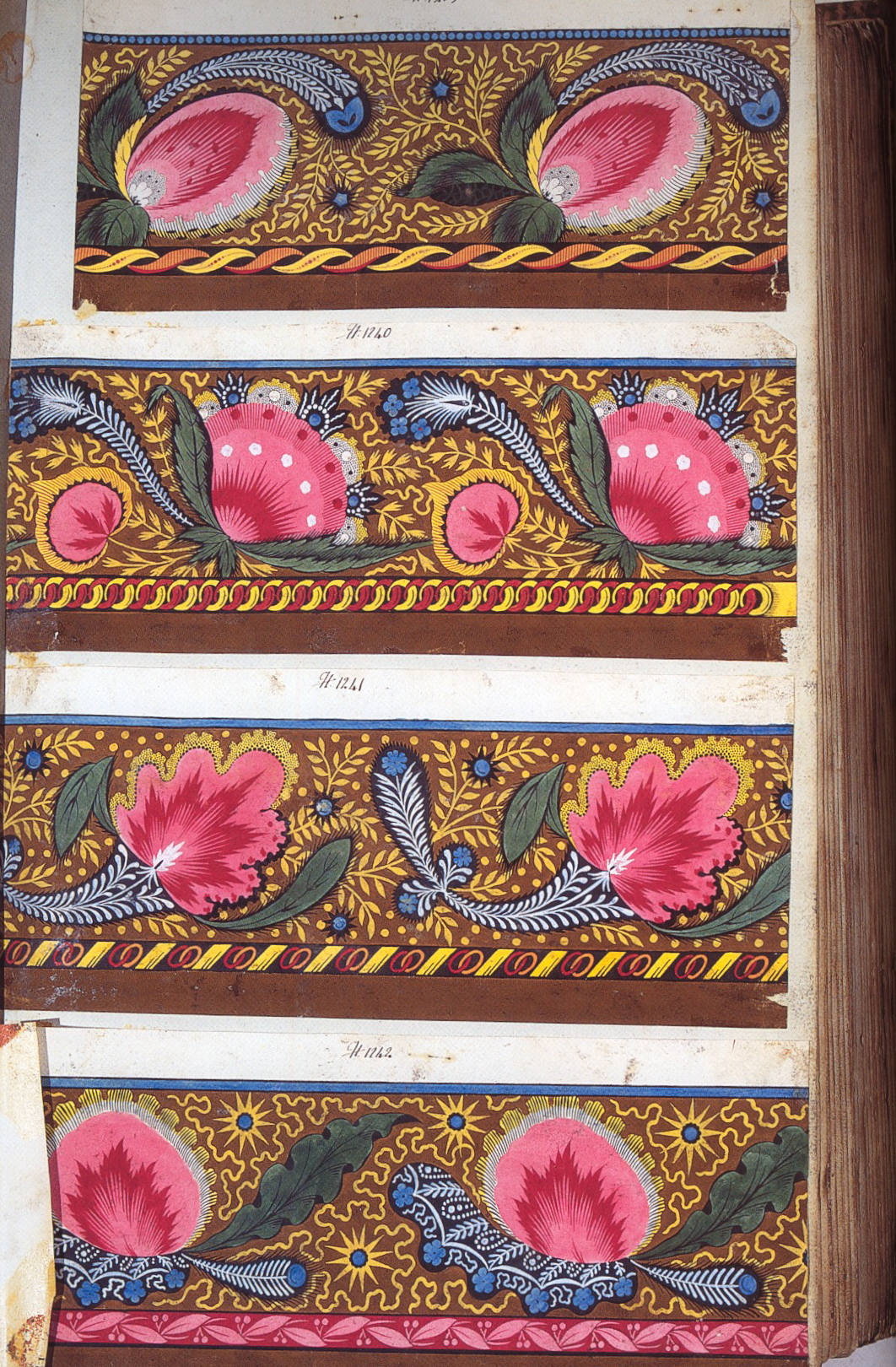

Textile and wallpaper designs were often collected in sample books—some were for companies and/or designers to keep track of their patterns, others were used to market the fabrics. Sample books for textiles, very popular in the 18th century through the 20th century, provide a wealth of information about the history of pattern design, dyeing techniques and the technical means of production. Often they contain swatches of the actual fabrics, shown in the various available colorways.

Wallpaper and border designs, Manufacture Dufour, Paris, early 19th century

Wallpaper and border designs, Manufacture Dufour, Paris, early 19th century

Designs for block print fabric, French, early 19th century

Designs for block print fabric, French, early 19th century

In 2008, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum mounted an interesting exhibition, Multiple Choice: from Sample to Product, that featured sample books for tableware, textiles for interiors and fashion, wallpaper, even buttons. Seeing these lovely books, which contain such a rich visual history, was quite poignant—in the contemporary design world, with electronic formats taking precedence, the paper sample book is truly a thing of the past.

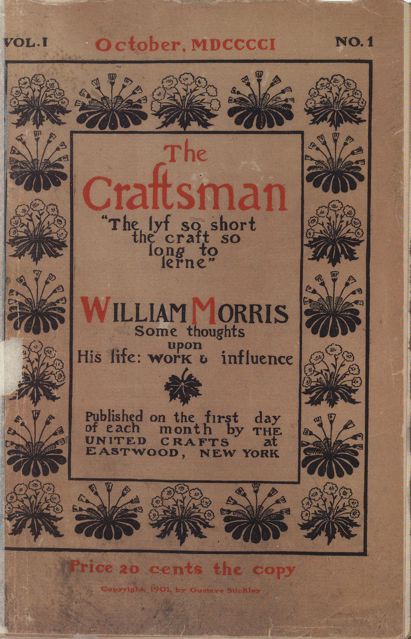

Among the sketches I’ve referenced in this post, many are by well-known designers, others are from an anonymous hand. Some designs were never turned into objects, others are still being manufactured today. But they all continue to live vibrantly on the page, their yellowed and tattered pages still emitting sparks of inspiration.

Wider Connections

The French Archive of Design and Decoration by Stafford Cliff

The English Archive of Design and Decoration by Stafford Cliff

Dagobert Peche and the Wiener Werkstätte, edited by Peter Noever